Miami and the Spanish American War – Part 3 of 3

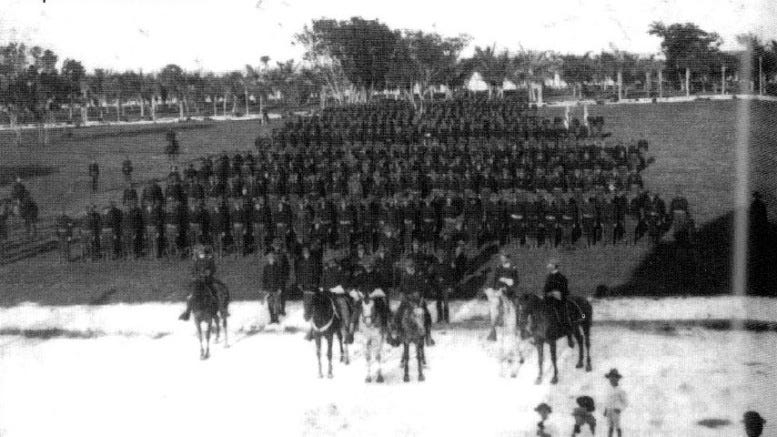

Part three of a three-part series on Camp Miami during the Spanish American War in 1898. Camp Miami was a training center established in the two-year old city of Miami in the summer of 1898.

As noted in the previous installment of this study, conditions in Camp Miami in the summer of 1898 worsened for 7,000 soldiers under the onslaught of heavy rainstorms, high temperatures, and humidity. One solider complained: “Here at Miami we have heat, mosquitoes and sandflies that beat anything we have ever met. We even hang our hats on the mosquitoes at night.” Another delivered a memorable, mordant lament for Camp Miami: “If I owned both Miami and hell,” he complained, “I’d rent out Miami and live in hell.” Indeed, “Camp Hell” became the soldiers’ sobriquet for their facility.

Miamians grew disillusioned with the antics of frustrated soldiers in Camp Miami. Theft on the part of the men constituted one of the problems. Riflemen used coconuts for target practice. Others upset townspeople by swimming naked in Biscayne Bay, which, arguably, could be described, at that time, as “the world’s largest bathtub!” A despondent soldier killed himself in the beautiful grounds surrounding the home of Julia Tuttle.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.