Miami's First Christmas in 1896

A description of the very first Christmas in South Florida after incorporation in 1896.

Christmas 1896 in the newly-incorporated city of Miami was euphoric for many of its estimated 1,000 residents, who exhibited feelings of pride in the transformation of a wilderness into an instant municipality in less than one year. Retail was much like today as the stores open for business on Avenue D, today’s South Miami Avenue in the downtown sector, offered Christmas specials. Tourists streamed into the nascent community and activities were planned for the entire population.

Our chief source of information on that first holiday season is the Miami Metropolis, a weekly newspaper that appeared each Friday. Since Christmas fell on a Friday that year, the journal came out one day early, on December 24. The Metropolis reported on the tourist influx, staying in the neophyte city’s few hotels and rooming houses, including the Hotel Miami, still in the final stages of construction, and at the smaller Connolly House. Guests arrived from far away states including Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, and Ohio.

While many visitors were arriving, some of the city’s most prominent residents celebrated Christmas elsewhere. John Sewell, one of the first retailers and a leading member of the Flagler organization, whose railroad birthed Miami in the spring of 1896, was spending Christmas with family in Kissimmee, while Frank Budge, another prominent businessman, celebrated the holidays in Titusville.

The newspapers also contained advertisement with holiday themes. Frank Budge’s hardware store, destined to become one of the city’s most important purveyors of hardware products for half a century, invited Miamians to “Come and See Our Large Stock of Christmas Goods, Fancy Crockery, Etc.” Its nearby competitor, Watson’s hardware store, boasted of holiday goods that were “ornamental, durable and serviceable,” and were of an “assortment that would be a credit to a Jacksonville house.” J.T. Feaster’s market encouraged readers to visit the store for their “fresh butter, eggs, chickens, and Christmas turkey.”

The “Mother of Miami,” Julia Tuttle, was behind the construction of the aforementioned Hotel Miami on Avenue D. That hostelry was one of the most important centers of holiday excitement. It hosted a “general Christmas tree.” Every child who came to the hotel on Christmas Eve was promised a present, contributed by generous Miamians. Additionally, the hotel was the gathering place for a Christmas Eve program, “the first of its kind in the history of Miami,” to be “rendered by children.” The Metropolis noted that “the ladies were working hard to make (the event) a success.” The journal also printed its wishes for all Miamians during that holiday season: “May no sickness or distress or adversity darken your doors this Christmas. May you be happy and gay.”

Four couples used the occasion of Christmas Eve to marry. Another couple, Charles J. and Phoebe E. Rose, celebrated their forty-seventh wedding anniversary.

Miami was already a racially segregated community, with African-American residents consigned to Colored Town, the black quarter. The black community was preparing on the eve of Christmas for a “comic parade” consisting of African American youth and “not so youthful” parade participants.

Literally looming over the city during its first holiday season was railroad baron and developer Henry M. Flagler’s hulking Royal Palm Hotel, then in its final stages of construction. Although the luxurious hostelry was not slated to open until January 17, 1897 (amid a grand celebration), it had already welcomed two guests on the eve of Christmas. John Jacob Astor, scion of one of America’s wealthiest families, and his young son, Vincent, were unofficial guests of the hotel at that time. While John Astor fished with Charlie Thompson, a renowned local fisherman, hotel employees hastily felled a nearby Dade County pine tree, moved it to the lobby of the hotel and decorated it with whatever ornaments they could locate. A hotel clerk remembered that Vincent Astor appeared on Christmas morning in a white sailor suit by the makeshift Christmas tree.

By then, the rest of the city was celebrating its first Christmas as an incorporated entity. The day passed without incident. John N. Lummus, a leading light who managed the Hotel Miami and later served as the first mayor of Miami Beach, celebrated his twenty-third birthday, while Margaret McCann, born one week earlier, was baptized by Father A.M. Fontan, a Jesuit Priest who was charged with organizing the Church of the Holy Name from which emerged today’s Gesu Catholic Church in downtown Miami. Three longtime residents of Lemon City, an unincorporated community lying five miles north of the Miami River, arrived in Miami from Key West en route to their homes in the first named community.

Residents of Cocoanut (sic) Grove, lying five miles south of Miami, celebrated Christmas in a variety of ways. The Union Chapel, an ecumenical house of worship, showcased its Christmas tree. The bathing casino near the shores of Biscayne Bay offered a concert. The nearby Peacock Inn provided guests with a Turkey dinner. Oddly, no Native Americans, who often visited Cocoanut Grove, were in the community on that holiday.

In the city of Miami, on the morning following Christmas, a destructive fire erupted in the heart of the business district on Avenue D, bringing the new city its first crisis. Ironically, in its December 24, 1896 edition, the Metropolis, insisted that Miami, which had been lucky up to that time in avoiding a conflagration, organize a fire company (a volunteer force) at once. In our next installment of this blog, we will study that fire and its impact on Miami.

Images:

Cover: Royal Palm Hotel nearing completion in 1896. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

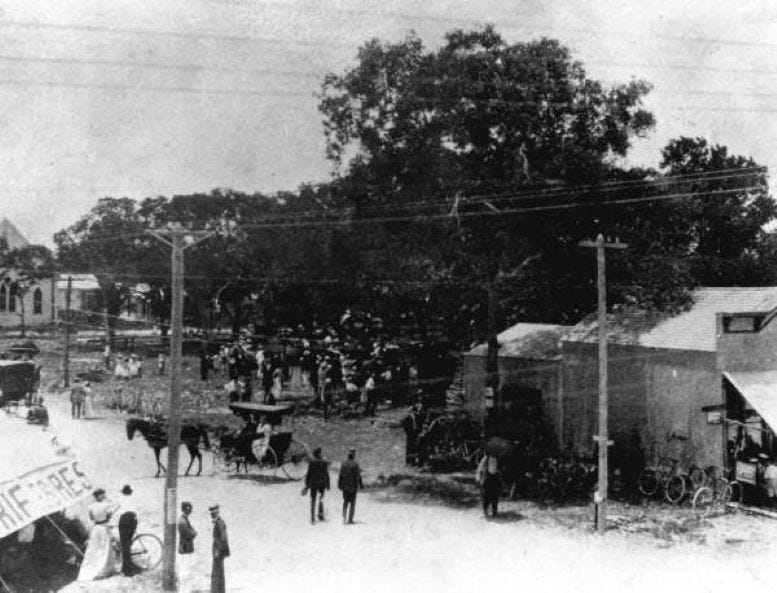

Figure 1: Miami's business district in 1896. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

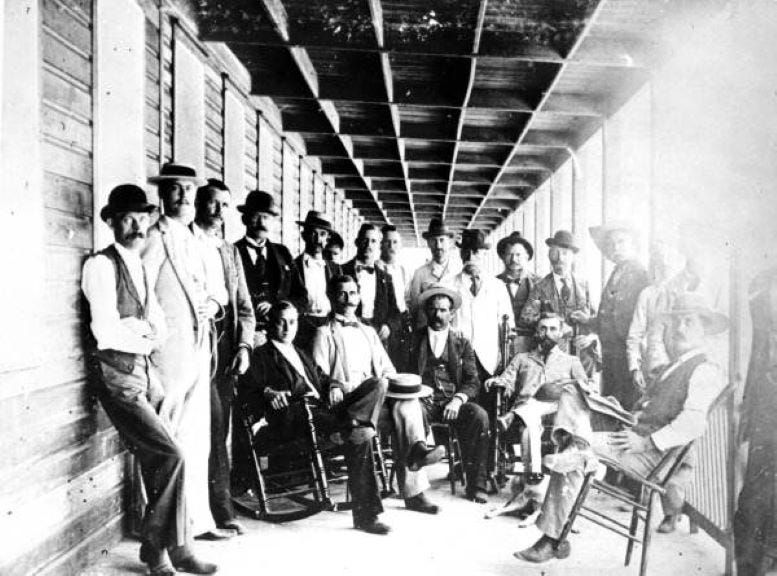

Figure 2: Front porch of Hotel Miami in 1896. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 3: Boarding house in Miami in 1896. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 4: Peacock Inn in Coconut Grove in 1896. Courtesy of Florida Memory.