Al Capone in Miami – Part 3 of 4

A four part series on Al Capone's time in South Florida. Part three shares how political figures tried to rid the area of Capone, and of his arrest and conviction for tax evasion in 1933.

For the first time in his life, Capone was serving time in jail. His sentence began in May of 1929 and by the spring of 1930 his jail time was approaching its end. After multiple attempts to appeal his year sentence, Capone would serve nearly a full year in jail. As he prepared to leave his jail cell in Pennsylvania, there was world-wide interest on where Capone would go after his release.

Chicago made it very clear that he would be arrested on site if he returned to the windy city. Threats from law enforcement never concerned Capone, but he knew that his enemies would be lurking in Chicago. While the rest of world waited for his release to see where he would end up, Capone chose to embark on a clandestine journey back to the “garden of America” for rest and relaxation.

Capone is released from Pennsylvania Jail

Al Capone and Frank Rio’s sentence was shortened by two months for good behavior. Both were scheduled for release from Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary at 12:01am on Monday, March 17th in 1930. The day was Saint Patrick’s Day. With great anticipation, several hundred onlookers and reporters began to congregate outside the main gate of the prison beginning at midnight. On the eve of his release, Capone was the big story of the day.

By the time the governor of Pennsylvania signed Capone’s papers at 11:10am on Monday morning, the onlookers began to grow at a staggering rate. It was estimated that there were as many as five hundred waiting outside the prison to get a glimpse of Capone.

However, the warden had pulled a fast one and transferred Capone to another prison the day before his release in order to avoid a mad scene outside of the Eastern State Penitentiary. None of the onlookers or reporters got what they came to see. Another reason for the transfer was to avoid any potential danger that Capone’s release could have attracted. By 2pm on March 17th, Al Capone was a free man.

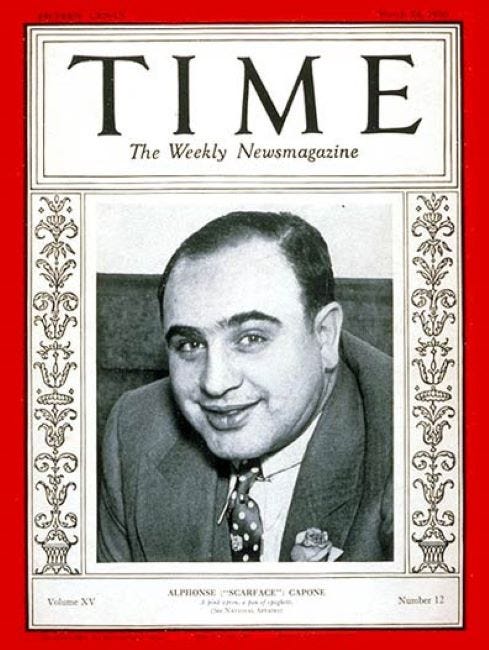

Al Capone was as popular as ever following his release. A week after he became a free man, Time Magazine featured Capone on the cover of the March 24th issue of the magazine. The attention heightened the concern in Florida that Capone would return and bring a lot of unwanted attention and danger to South Florida.

While there was no definitive confirmation that Capone was intending to return to his Palm Island home, it didn’t take long for the Florida governor, Doyle E. Carlton, to take official action to make it difficult for Capone to return to the state. At the urging of Carl Fisher, the governor issued a statement banishing Capone from returning to Florida on March 19th, 1930.

Governor Carlton instructed law enforcement to detain Capone on site and escort him to the state border with instructions not to return. Governor Carlton’s instructions had set the tone for what Capone could expect from officials in Florida throughout the course of 1930.

Capone’s Palm Island Home Raided

On March 20th, 1930, Al Capone’s home was raided by Dade County Sheriff M.P. Lehman and Miami Beach Chief of Police R.H. Wood, based on information that Ray Nugent, a bond jumper from Ohio was suspected of being at 93 Palm Island. Ray Nugent was wanted in Toledo and Cincinnati on a variety of charges, including second degree murder.

Several months before Al Capone was released from jail, Frank Capone and two women were pulled over in the company of Ray Nugent. Nugent was stopped for speeding and told the arresting officer that he was staying at Capone’s Palm Island home. After Nugent skipped bail, the officers got a warrant to search Capone’s home. The raid took place prior to Al Capone returning to Florida.

The only person that they found in the home was Frankie Newton, the caretaker of the residence. Although they did not find Nugent, they did find three bottles of liquor, a couple bottles of champagne and a bottle of wine. Newton mentioned that the others had left for the beach a short time before the raid. There were six officers left outside the gate to wait for the men.

The officers later arrested two of Al Capone’s brothers, John and Albert Capone, along with three other men, when they arrived back to the home. The men were arrested on vagrancy charges, with John Capone and Frankie Newton also charged with possession of alcohol. One of the three other men was Gunner Jack McGurn, right hand man to Al Capone in Chicago gang activities. He gave his name as John Vincent.

The charges were dismissed on August 1st, 1930, by Dade County Judge W.F. Brown. The ruling was based on the grounds that information filed against the men did not follow the language of the law. Ultimately, McGurn, under the name of John Vincent, confessed to owning the liquor and ended up paying a fine of $500.