An Unlikely Partnership - Fisher Meets Collins

The story of how Carl Fisher met John Collins which started a partnership that led to the founding of the City of Miami Beach, and the completion and opening of the Collins Bridge on June 12, 1913.

Although Carl Fisher told his wife, Jane, it was his intention to retire when they bought their home on Brickell Avenue, his retirement wasn’t meant to be. Within a few weeks after the Fisher’s chance encounter with John Collins on Indian Creek, Carl began to mosey around Miami to learn about his new winter home.

During his exploration of Miami, Fisher came across a rather curious development. He noticed a wooden structure that jetted out from Miami into Biscayne Bay. He also noticed that the bridge seemed to stop short of the island that he had explored a few weeks earlier by boat. The bridge to nowhere really tickled his curiosity. Carl continued his walk until he got to the office of an old friend.

The Risk Taking Quaker

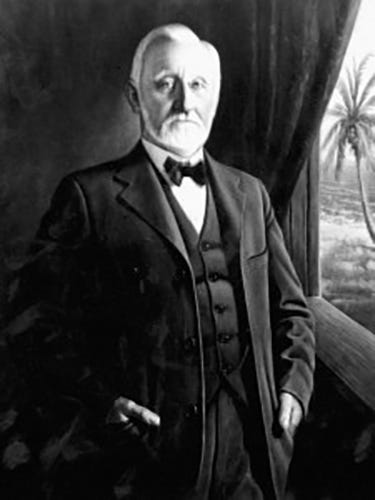

John Collins was born on December 29, 1837 in Moorestown Township, New Jersey. He was a direct descendant of the first Quaker colonists who settled in western New Jersey in 1677. John was a farmer and horticulturalist. He was one of the founders of the state horticultural society in New Jersey.

Collins experimented with various kinds of fruits. He was ahead of his time using current technology and the latest farm equipment to make farming easier. Collins included his sons and son-in-law into the flourishing family farming business.

It was during a pomological meeting in New Orleans where Collins met Elnathan T. Field in 1883. Pomology is a branch of botany that studies and cultivates fruit. Field got him interested in coconuts.

Field explained that he was investing in a coconut plantation on a peninsula in southern Florida. He had a partner by the name of Ezra Osbourn and invited Collins to invest. Site unseen, Collins invested $5000 to be a part of the venture. For a horticulturalist from New Jersey, coconuts seemed very exotic and intriguing.

Collins was never shy about taking risks. Besides his blind investment in the coconut plantation, Collins had also invested in a Carolina gold mine and other enterprises that his family questioned. Ten years would pass before Collins ever inspected his coconut plantation investment.

Collins Travels to Florida

John Collins made his first trip to Florida in 1890. He was 53 years old and he visited Hypoluxo. However, it wasn’t until 1896 that Collins decided to check out the coconut plantation investment he made with Field and Osborn years earlier.

The development of the plantation did not yield what the partners had expected. Rather than being discouraged by a bad investment, Collins looked to the future to figure out the best crop for the island. In 1907, seven years after the death of Ezra Osborn, Collins bought a half interest in the lands originally shared by Field and Osborn, running from Jupiter to Norris Cut.

Collins was now an equal partner with Fields. However, the two men disagreed on the best use of the land. Field wanted to play it safe and plant grapefruit. Citrus crops were a proven commodity in Florida and Field felt that a grapefruit crop would help them recoup their investment. Collins wanted to plant a new and exotic fruit called alligator pears. The more common name for this fruit is avocado.

Collins was very accustomed to getting his way and making the final decision. He insisted on planting avocados. It was shortly after the forming of the partnership that he began planting 2945 avocado trees. The decision ended the partnership with Field. Collins purchased Field’s interest.

More Investment Needed

At the age of 70, Collins found himself the sole owner of a five mile strip of land between the Atlantic Ocean and Biscayne Bay. The land would include roughly everything from Fourteenth Street to Sixty Seventh Street on Miami Beach today.

Collins only used part of the land he owned for farming. He focused his avocado crop on the elevated land just west of Indian Creek near today’s 41st street. The farm was a mile long and about seven hundred feet wide.

At first, it was estimated that the clearing of the land of pine and palmetto would cost $300 per acre if done manually. Collins ordered sixteen ton tractors with knife-bladed wheels to chop up the pine roots and special equipment to dig them up. The cost of clearing the land was dropped to $30 per acre.

The clearing on the land was only one hurdle. The avocadoes needed special care for both growth and shipment. Moving the harvest from the beach to downtown Miami also presented problems. Lastly, Collins needed time for the avocado trees to bear fruit.

He experimented with bananas, mangos, tomatoes, corn, potatoes and peppers that he planted between rows of avocado trees. These crops could be sold in Miami to help defray expenses.

By 1911, Collins needed more money to keep the farm going. His irrigation system was inadequate and he needed a better approach to getting the crops from the farm to Miami. His solution for his logistics problem was to build a canal from the head of Indian Creek through the mangroves to the bay. It would cut the ten mile trip to Miami in half. He informed his children in Moorestown that he was going to invest more money in the farm.

A Family Endeavor

In remembering their father’s past bad investments, John Collin’s adult children were skeptical. However, they knew that once their father had an idea, he can be very insistent and stubborn. The entire family asked to see this farm before agreeing to go along with the idea of investing more money.

All seven of Collin’s children and their spouses agreed to come to Miami. In 1911, the family traveled to Miami following a vacation in Havana, Cuba. The city of Miami was only fourteen years old, but had a population of ten thousand, not including winter visitors.

The Collins and Pancoasts (Thomas and Katherine Pancoast, John Collin’s daughter), were shocked to find out that Miami was not on the ocean. They assumed it was a lot like a New Jersey shore town similar to Seaside Park.

After seeing the farm on the peninsula, the Collin’s children agreed that the land may have prospects as a farm, but they were skeptical of whether the reward would outweigh the risk. However, John Collins was stubborn and he was not going to change his mind about the investment needed.

It wasn’t until the children looked at the island from across the bay in Miami that they found a compromise. They agreed that the land would make a great seaside resort, much like New Jersey’s barrier beaches.

The Collins children convinced John that part of the land could make a good seaside resort similar to Atlantic City. John was not very interested in real estate, so he let his children determine the best way to proceed in managing the portion of land that would be developed. The family created a firm called Miami Beach Improvement Company and the whole family invested.

The agreement called for John to keep up the land that would continue to be used as a farm. Katherine and Thomas Pancoast would move from New Jersey and would run the newly created real estate firm. The Pancoasts were the only ones willing to uproot themselves from New Jersey and move to the wilderness to run this new venture.

In addition to the canal that was needed, the family agreed that there needed to be a bridge to connect the mainland to the beach. With the money raised to start the company, a lot of investment went into what became known around town as “Collin’s Folly” (the Collins Bridge).

The Collins Bridge

By the summer of 1912, both the Collins Canal and Collins Bridge were under way. The fill dug for the canal would later be used to make a roadbed to the bridge. The building of the bridge presented one challenge after another.

First, the Biscayne Navigation Company, who ran two ferries from Miami to the southern tip of the beach, protested the issuance of a franchise, by the county, to build the bridge. They felt that their business of running passengers to the bathing casinos from Miami would be undermined.

However, Collins had the most influential lawyer in town. An Indiana man by the name of Frank Shutts represented Collins and family. Shutts argued that because the ferries could not carry the weight of an automobile across the bay, automobile service to the beach was being denied full use of the land without the availability of a bridge. The county commission agreed and granted the franchise needed to build the bridge.

Once construction for the bridge began, it became clear that the pilings to support the bridge would need a jacket of cement if the bridge were to last in the salt water. This unexpected process would cost a lot more than was budgeted. The costs per mile soon reached $50,000.

It wasn’t long before the Collins family had reached their credit and resource limit to finance the bridge. In November of 1912, the family had built the longest wooden vehicular bridge that led nowhere. Discouraged, John Collins perched himself on one of the bridge girders to contemplate what to do next. He looked out at his partially finished project without options on how to finish his bridge. It became what Carl Fisher termed “a skeleton in the bay” during his walk along the Bayfront.

Frank Shutts Suggests a Project

The old friend that Carl met with the day he explored Miami was Frank Shutts. Frank was an attorney who was brought down to Miami to be a bank receiver in 1909 by Henry Flagler. Born near Aurora, Indiana and a graduate of DePauw University Law School, Shutts was a native son of Indiana.

On December 1st, 1910, with a loan from Henry Flagler, Shutts acquired the Miami Evening Record and renamed it to the Miami Herald. He owned the paper until he sold it to John S. Knight on October 25th, 1939. Frank Shutts also founded Shutts & Bowen law firm.

Frank and Carl reunited after Fisher’s decision to retire in Miami. During the course of their conversation, Fisher asked about the bridge. Frank explained that the bridge was being built by an old man who was one of Shutt’s clients, John Collins. He further explained that Collins is a seventy five year old man who has more courage than money. His intention is to extend the bridge from Miami to the beach.

Shutts then suggested to Fisher that he should consider helping the old man. He pointed out to Fisher that he was too young to retire, and that an investment in the bridge could give him a project and something to do while wintering in Miami.

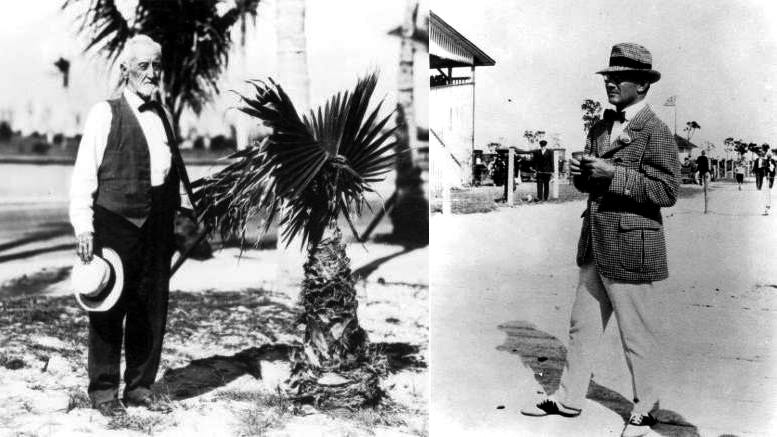

As Fisher left Shutts office, he was quiet and pensive. He walked back over to the bridge when he noticed the elderly Collins high up on one of the girders just swinging his legs. Fisher approached him and introduced himself. The two men sat together and talked, and as Jane Fisher put it in an interview with Polly Redford in April of 1967, “that was the beginning of Miami Beach”.

The Rest is History

Carl Fisher agreed to loan Collins $50,000 and asked for a bonus of two hundred acres of land from the south end of Miami Beach Improvement Company’s land. The land was a mile long strip, and 1800 feet wide from ocean to bay.

John Collins and his son-in-law, Tom Pancoast, accompanied Fisher to inspect the land in Fisher’s speed boat. Fisher traveled up the Collins Canal and docked near a portion of Fisher’s newly acquired land. While they felt Carl Fisher drove his boat like a nut and were concerned with what he was doing to their newly dredged canal shore line, they quickly appreciated Carl’s vision. Fisher jumped out of the boat and began virtually laying out a city with hotels and polo fields. Carl Fisher was a man of big ideas supported by an even bigger vision.

With Fisher’s financial backing, the Collins Bridge would be completed and officially opened on June 12, 1913. The 2.5 mile long wooden bridge would be described, by Thomas Pancoast, as the longest vehicular wooden bridge in the world. However, the bridge would only remain in operation until 1925. It would be replaced by today’s Venetian Causeway.

Carl Fisher would increase his land holdings through dredging and fill, as well as, providing help to the Lummus brothers, who owned a significant portion of the southern part of the island. Collins, Pancoast, Fisher and the Lummus brothers would work together to develop and promote what would become the City of Miami Beach.

Despite differences in generation and life experiences, the Fisher and Collins partnership worked because of what they had in common. Both were stubborn, persistent and obsessive about their vision. It has been said that history gives us the people we need when we need them most. The Fisher and Collins story proves that history also forges well-timed partnerships as well.

Resources:

Book: “Billion-Dollar Sandbar”, Polly Redford

Interview Transcript: “Interview with Jane Fisher”, Polly Redford

Book: “The Pacesetter”, Jerry Fisher

Book: “The Fabulous Hoosier”, Jane Fisher

Book: “Sunshine, Stone Crabs and Cheesecake – The Story of Miami Beach”, Seth H. Bramson

Book: "Miami Beach", Howard Kleinberg