Birth of The Magic City - Miami

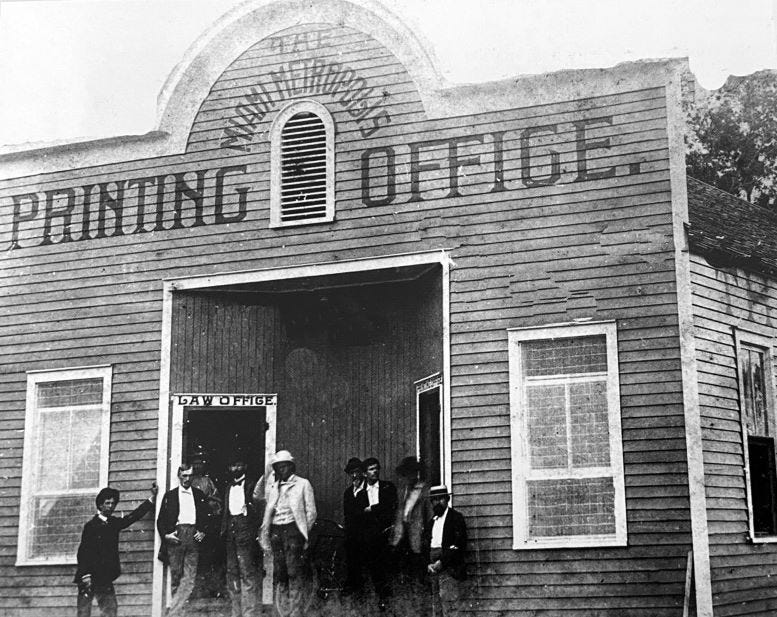

The story of Miami's incorporation on Tuesday, July 28, 1896.

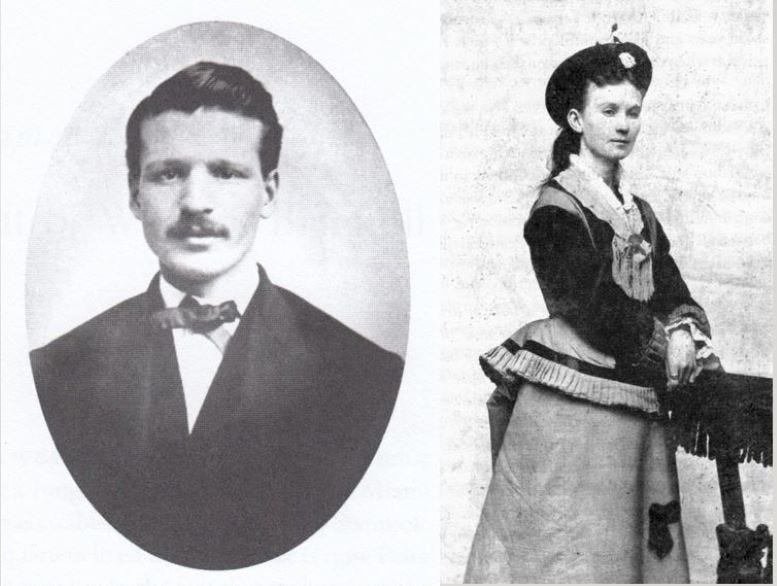

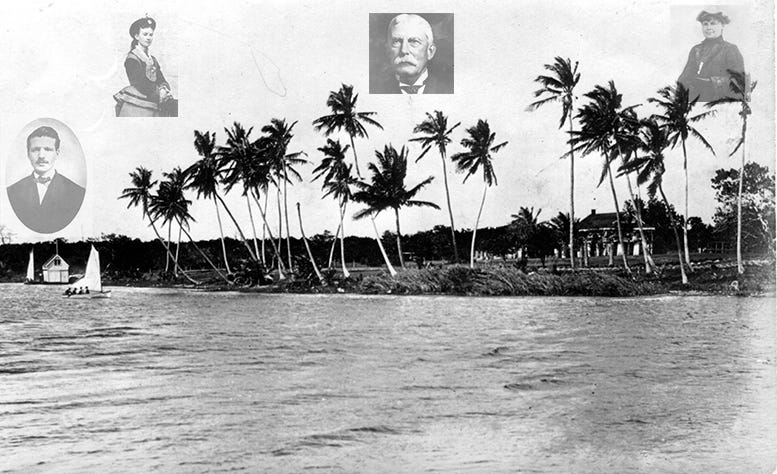

By the spring of 1896, the once-quiet outpost along the Miami River was bustling with activity, as preparations were underway to fulfill Julia Tuttle’s premonition of the small outpost along Biscayne Bay transforming into “one of the largest, if not the largest, cities in all the South.” A lifelong dreamer, Tuttle’s hopes for a thriving city were rapidly taking shape, with her long-held vision on the verge of becoming reality.

After the devastating freezes of 1894 and 1895, Henry Flagler dispatched James Ingraham south from Palm Beach to assess how far the cold had spread. Upon reaching Miami, Ingraham was welcomed by an old acquaintance, Julia Tuttle, who handed him a pristine orange blossoms, its leaves untouched by frost, to include with the plant samples he was gathering as proof that the frigid temperatures had spared the banks of the Miami River.

Based on what Flagler learned from Ingraham’s findings, he decided to travel to the region and see it for himself. After his visit, he entertained an offer from Tuttle and the Brickells for land in exchange for his investment to construct a fine southern city. In exchange for land offered by Tuttle, as well as William and Mary Brickell, Flagler agreed to extend his railroad to Biscayne Bay, build a luxury hotel, and construct a town around it. The wording of a “town” would later be debated as the appropriate designation of the municipality being built along the Miami River.

Land Granted to Henry Flagler

At the time Henry Flagler agreed to extend his railroad and help build a city, Julia Tuttle owned much of the land on the north side of the Miami River. As detailed in Miami, The Magic City by Arva Moore Parks (page 82), Tuttle conveyed half of her holdings, about 300 acres, to Flagler. This included 100 acres along the bay and riverfronts, excluding her 13-acre homestead and select parcels within what would later become the business district. In a shrewd move, Tuttle arranged the land transfer in alternating lots, ensuring the area’s development while maintaining a stake in its future growth.

The contract between Julia Tuttle and Henry Flagler included a specific condition: the luxury hotel he planned to build, the Royal Palm Hotel, could not obstruct her view of Biscayne Bay. Tuttle’s homestead, which once offered that unobstructed view, today is the site of the Miami Convention Center and the downtown Hyatt.

Between the hotel and the north bank of the Miami River, a beautifully landscaped garden, designed by Henry Coppinger Sr., was planted during the the construction of the hotel in 1896. The Royal Palm Hotel site was redeveloped into the Monarch at Met apartment complex, while the former Royal Palm Gardens is now the site of an assortment of buildings including the Epic Hotel and Aston Martin Residences.

The 66-story Aston Martin Residence was constructed on a 1.25-acre parcel of land that cost the developer $125 million to acquire. The land is located along the north bank of the Miami River and provide the value of great water views, but the land could have been acquired for $1.25 per acre a hundred years earlier.

Once the terms were agreed between the different parties, Flagler signed a separate agreement with the Brickells than the one he signed with Julia Tuttle. The Brickell family included parcels on the south side of the Miami River as well as land in Fort Lauderdale. Like Tuttle, Mary Brickell negotiated a carve out of land that was to remain with the family. Flagler acquired acreage west of today’s South Miami Avenue, and the Brickells kept everything east of that thoroughfare.

It was during negotiations that Henry Flagler verbally agreed to construct a bridge over the Miami River connecting the north side with the south side, but later the family, particularly William Brickell, expressed his frustration with the progress of development on the land they donated to Flagler. The bridge was never constructed by Flagler’s people as promised, and it would be years later when a bridge finally connected downtown Miami to Brickell Avenue in 1928.