Booker T Washington School in Overtown

Booker T Washington, Miami's first segregated black high school, opened on February 28, 1927, at 1200 NW Sixth Avenue in Overtown. The original building was replaced with a modern building in 1989.

By the peak of the great building boom in 1925, the population growth of Dade County had more doubled since the census of 1920, necessitating the need for a significant number of new schools to serve neighborhoods that became overwhelmed with the in-migration of new families. Communities with schools needed money to expand existing buildings to accommodate the growing student population, and neighborhoods without educational institutions required funding to construct new schools.

During a time of Jim Crowe era segregation, the black community in Overtown did not have any options to send their children to high school. By 1924, black students could attend Dunbar School on Twentieth Street to attend grades first through eighth, but their education ended after graduating from middle school. If families wanted their children to earn a high school diploma, they would have to send them out of the county to continue their education beyond the eighth grade. This changed when Booker T Washington high school opened in February of 1927.

Bonds Approved for New Schools in 1926

By the spring of 1926, South Florida had grown so rapidly that there became a need to provide more schools for the growing student population. From March 1 through May 23, the residents of Dade County approved school bonds for over $4.1 million to construct new, or expand existing, schools throughout the county, but primarily in and around the City of Miami, which was the fastest growing quarter of the county. Factoring inflation, total sum raised during the bond campaign would amount to over $67.5 million in 2023 dollars.

The school bonds would account for the erection of twenty-nine new schools throughout the county which would impact the construction or expansion of institutions such as Citrus Grove elementary, Shenandoah and Allapattah junior high schools. However, the biggest projects during this period were the construction of the high schools. Lemon City, Miami, and Ponce De Leon high schools were examples of some of the buildings that were funded during the 1926 bond campaign.

Perhaps the most consequential institution built as part of these bond issues was the eventual Booker T Washington high school. Since Article XII, Section 12 of the 1885 Florida constitution legitimized school segregation by stating “white and colored children shall not be taught in the same school, but impartial provision shall be made for both,” this school was constructed to become the first high school for black students living in Dade County. The policy of racial segregation of schools ended when the current Florida state constitution, ratified on November 5, 1968, ended this provision.

Prior to the opening of this school, black families had to send their children north to cities such as Tallahassee, Atlanta, or Tuskegee, Alabama, to get a high school education. Each of these cities had black colleges that offered programs with a high school curriculum for students living in school districts in the south that did not offer educational opportunities beyond the eighth grade.

Marvin Dunn, in his book “Black Miami in the Twentieth Century”, explained that one of the reasons that there were no high schools in Dade County for black children prior to 1926 was that “southern whites generally believed that blacks were best suited for manual or domestic work, making it wasteful to spend public money on education beyond the eighth grade.”

The location of the new black high school, initially referred to as the ‘George Washington School’, was chosen along NW Sixth Avenue, between Twelfth and Thirteenth Streets, in Overtown. While the new high school was located within the boundaries of the segregated black section of ‘Colored Town’, another reference to today’s Overtown, there were plenty of people within the surrounding white community that objected to the idea and location of the school.

Resistance and Threats

The idea of a black high school along NW Sixth Avenue was not new when construction began for the Washington School. Several years prior to the bond drive campaigns of 1926, the school board considered building a ‘negro school’ at the same location but was not pursued when, as a writer for the Miami Daily News described as “agitation for the plan was so strong at that time that the project was abandoned.”

Upon the announcement of the resurrection of the plan to build a high school in the same location, the same opposition developed. In February of 1926, representatives for the Northwest Fifth Avenue Improvement Association called on Miami City Manager, Frank Wharton, to ask the school board to stop work on the school because they objected to the location. Wharton told the association members that the school board was within their rights to erect the school because it was within the boundaries of the ‘negro section’.

Charles M. Fisher, superintendent of public schools, asserted that there were no legal barriers to the construction of the school at the chosen location. The chief complaint by the association was that the back of the school would adjoin a ‘white district’. As a compromise to the association, it was reported by the Miami Daily News that the superintendent suggested that a twenty-foot concrete wall be built around the school grounds to overcome the objection to its location. Ultimately, this suggestion was never implemented.

There were threats and attempted sabotage of the project to keep it from being finished. In March, the onsite office of the general contractor, Smalridge Construction, was lit on fire but extinguished before incurring any significant damage. In May, George Smalridge received a phone call from someone threatening to ‘dynamite the school’ if construction was not stopped.

Once stories began to circulate of some of the threats to the project, a night watchman, armed with a sawed off shotgun, began guarding the construction site when workers were not present. Within two months of the threat to dynamite the building, part of the structure collapsed leading many to believe it was caused by malfeasance.

Partial Collapse of School Building in June of 1926

By Monday morning on June 28, 1926, the school building was beginning to take shape. Workers began pouring cement on the third level when, at 10:15am in the morning, the floor underneath them gave way causing a partial collapse of the building which hurled the workers on the third level to the ground.

A reporter for the Miami Herald covering the story wrote:

“Eight workman, six negroes and two white men, fell the three floors but only one of them was injured seriously. At first it was believed that others on the ground might have been buried in the debris and frantic digging followed until a timekeeper reported all accounted for.”

The tragedy could have been much worse, but the event led to a lot of questions about what caused part of the building to crumble. There were a mix of eyewitness accounts about what happened to trigger the collapse. Many stated they heard an explosion right before the floor dropped below them, but others claimed that they didn’t hear anything before the crash.

The general contractor and supervising architect, J.H. Sculthorpe, vouched for the workmanship and design, suggesting that only sabotage could explain the accident. Sculthorpe, whose office was located in the Townley Building in downtown Miami, said that: “he had 30 years of experience with construction work and that the collapse was not due to faulty construction. Something happened out there, and I don’t see any chance of ever finding out what it was.” George Smalridge, the general contractor, said there was nothing wrong with the construction of the building, but he didn’t think it was dynamited, despite the warning he received four months earlier.

The City of Miami’s building inspector, A.H. Messler, ordered samples of the concrete and surrounding materials to be collected and sent to a nearby local laboratory to find out whether dynamite was used in an attempt to destroy the building. Sections of the concrete beam at the center of the collapse was sawed out and sent to Pittsburg Testing Laboratories at 2250 NW Second Avenue for a forensic evaluation.

Meanwhile, news of the building collapse spread quickly throughout the surrounding neighborhoods. More than one thousand onlookers gathered around the building to witness the search and rescue operation. Two hours after the collapse, there were still several hundred people still loitering on the grounds to watch the clearing of the wreckage. However, results from the laboratory testing would not be available for more than a week after the collapse.

Results of Investigation

On July 7th, 1926, A.H. Messler released the following statement to share the results of the investigation:

“E.A. Sthuhrman, representing the Dade County Board of Education, and myself have made a complete examination of the collapsed portion of the Washington school and find that it was caused by failure of beam L-5 at column 93, due to poor mixture of concrete at that point. Balance of concrete apparently good. The weight of the entire third floor, the super-imposed form-work, and the partly concreted slab of the roof falling upon the second floor, sheared off beam L-5 was typical for second and third floors."

Navigating through the technical jargon, the building inspector concluded that the cause of the collapse was not due to dynamite or sabotage. The laboratory did not find any evidence of dynamite in the sample collection which led the investigation team to evaluate the quality of the cement. Messler also reassured the public that other parts of the building were inspected for weak points and concluded that the rest of the structure was sound and that the project was cleared to resume.

Despite the statement by the building inspector, many in the black community did not buy the official explanation. Given the threats and resistance to the project, the theory of the school collapsing due to a dynamite explosion became the unofficial explanation for how part of the school imploded on June 28, 1926.

Hurricane Delayed Project Further

School administrators had hoped the building would be finished and the high school ready to open by the fall semester, but the great hurricane of September 1926 derailed those plans. The work on the building to rebuild the portion of the structure that collapsed was nearing completion when the category 5 hurricane hit Miami on September 18th. The cyclone did not spare any part of Miami and caused significant damage throughout the metropolitan area including Overtown.

After assessing the destruction of the school, the general contractor filed a building permit for $20,000 to repair the damages caused by the storm. Compounded with having to make up time to rebuild the partially collapsed portion of the building, the workers now needed additional time to repair damage from the hurricane.

Given the impact the hurricane had on the area and the building, when the school finally opened in 1927, the school board selected ‘Tornadoes’ for the school nickname as an homage to the storm. The word ‘tornado’ was used interchangeably with ‘hurricane’ when describing storms of this nature. The University of Miami selected their nickname of the ‘Hurricanes’ for the same reason.

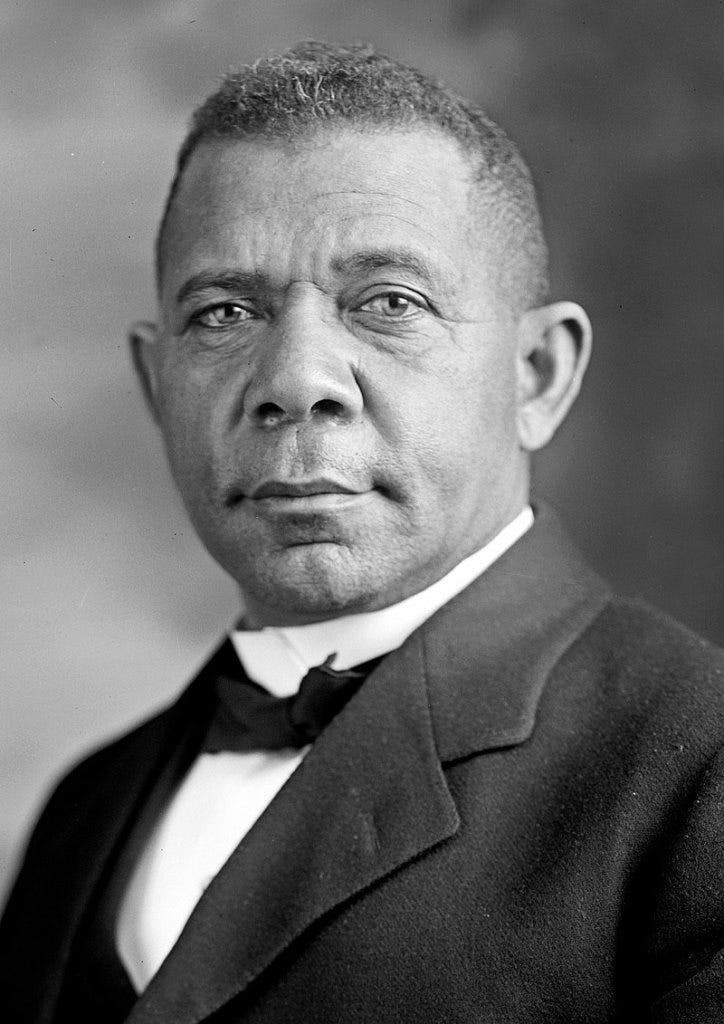

Booker T. Washington

While the school being constructed in Overtown was referred to as the ‘George Washington Negro School’ for much of 1925, that changed just prior to the opening of the school in February of 1927 when it began being referred to as ‘Booker T Washington High School’. It isn’t exactly clear when this change was implemented, but it did occur prior to the official opening of the school.

Born into slavery on April 5, 1856, Booker T Washington became one of the most important leaders of the black community in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Washington was an educator, author, orator, and advisor to several Presidents of the United States. He was a founder of the National Negro Business League and leader of the Tuskegee Institute, which, among many other programs, provided a curriculum for black students who didn’t have opportunities for a high school education in their home counties. Such was the case for students in Dade County prior to the opening of Booker T Washington High School in 1927.

Booker T Washington became the leading voice of former slaves and their descendants in the fight for civil rights and economic opportunity. It was only natural that the first black high school in Dade County be named for a leader of Washington’s stature. Many other schools throughout the mid-Atlantic and southern states were also named and dedicated for the iconic educator and civil rights leader.

School Opened in February of 1927

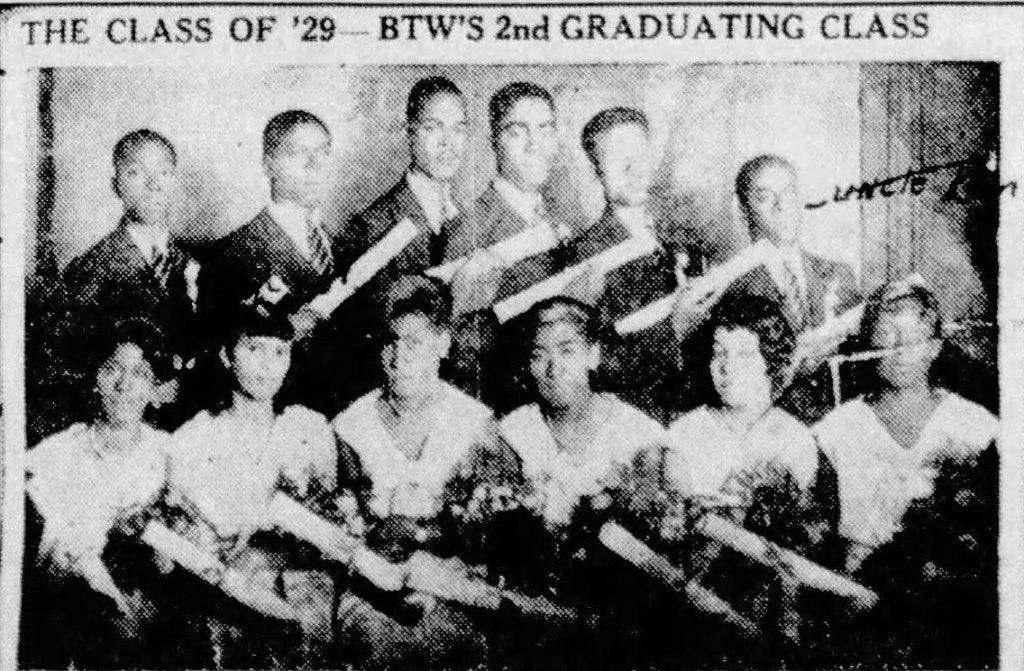

Booker T Washington High School officially opened on Monday, February 28, 1927 to become the first black high school in Dade County. Many of the first students to attend the school remember participating in the march from Dunbar junior high school to Booker T Washington the day it opened. In an article in the Miami Herald more than sixty years after the school opened, Dr. James Johnson, one of twelve students who were part of the second graduating class, recalled:

“The day Washington opened, 500 of us marched from the old Dunbar to Washington and I remember Mary McLeod Bethune spoke at our commencement.”

The high school building cost $306,000 to construct and was three stories in height with an auditorium, forty-three classrooms, and rooms for cooking, sewing and laundry. The school staffed nineteen teachers and could accommodate up to two thousand students, but opening enrollment was one thousand and sixty pupils at the end of the first day. Through the years, the school drew students from as far as Key West and Pompano Beach. Despite the building being brand new, the students were issued used books that were reallocated from other schools in the district.

In the 1930s and 1940s, celebrities such as boxing champion Joe Louis and entertainer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson visited the school and donated money. Years later, Cassius Clay, who was better known as Muhammad Ali, and Harry Belafonte appeared at the school. The building would serve the Overtown community as a high school for forty years before the movement to racially integrate schools within the Dade County school system.

Integration in 1967

By 1966, the civil rights movement in South Florida led to the beginning of desegregation of schools within Dade County. In 1967, Booker T Washington high school merged with Jackson high, which had already been integrated a year earlier, and was designated as a junior high school as part of the merger. Desegregation of schools throughout the south led to some of the black high schools to be converted to middle schools, which was the fate of Booker T Washington in 1967.

Booker T Washington would operate as a junior high school until the dawn of the twenty-first century when it returned to its academic roots and was converted back to a high school in August of 1999. By that time, the original school building had been replaced after sixty-two years of service when it a new school building opened in 1989.

New School Building in 1989

By the early 1980s, the Dade County school board recommended that the original Booker T Washington school be replaced. The building was fifty-five years old at the time and was beginning to show its age and obsolescence. It did not have air conditioning and many of the other modern features found in newer schools across the county. While the recommendation for a new school was made in 1982, the replacement building was not started until 1989, when a new structure was constructed across the street from the original school building.

The new school would cost $24.8 million to build and would officially open in August of 1989. After the old school building was vacated, and asbestos was removed from the walls within the structure, demolition of the building commenced. On November 12, 1989, Dade County’s first black school building was razed, marking the end of an era.

Impact of the School

During the bond drive of 1926, the voters of Dade County invested over $4 million for the addition of 498 rooms to the school system, including 276 new classrooms and seven new libraries. While some of the schools constructed as part of that initiative have been renovated and still stand today, such as Miami High School and Shenandoah Middle School, the original Booker T Washington building only stands in the memories of those who attended the school from its opening in 1927 until its demise in 1989.

Booker T Washington, the educator, once said “I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life as by the obstacles which he has to overcome while trying to succeed.” The school that carried his name in Dade County had to overcome more than its share of ‘obstacles’ from the onset and during its sixty-three years in Overtown.

The alumni who went on to become doctors, such as Dr. James Johnson (class of 1929), historians, such as the founder of the Black Archives, Dorothy Jenkins Fields (class of 1960), professional athletes, such as Miami Dolphin’s legend Larry Little (class of 1963), as well as other prominent roles within the community, fondly remember the educational foundation they received at Booker T Washington and how that experience helped shape their personal success. It was through the success of the students who attended Booker T Washington that the words of the orator came to life.

Resources:

Book: “Black Miami in the Twentieth Century”, by Dr. Marvin Dunn

Book: “Up From Slavery – An Autobiography”, by Booker T Washington

Website: Florida State University Law School – Florida 1885 Constitution

Miami News: “8 Hurt as Miami School Falls”, June 28, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Test May Fix Blame”, June 30, 1926.

Miami Herald: “Concrete was Faulty”, July 7, 1926.

Miami News: “Storm Damage Boosts Permits”, October 16, 1926.

Miami Herald: “New High School to Open Monday”, February 25, 1927.

Miami Herald: “New School Offers Opportunity to Many”, March 2, 1927.

Miami News: “Boom Gave Boost to New Schools”, June 22, 1985.

Miami Herald: “School Opens Doors – but Not All of Them”, July 9, 1989.

Miami Herald: “Booker T. Grads Preparing Book of Memories”, July 30, 1989.

Miami Herald: “The Return of Booker T Washington”, September 3, 1989.

Miami Herald: “Booker T Looks Back and Forward”, November 11, 1989.

Miami Herald: “Original Booker T. Falls to Bulldozer”, November 12, 1989.

Miami Herald: “Booker T Alumni Re-Create March”, November 13, 1989.

Miami Herald: “Alumni Look Back in Love”, June 7, 1990.

Miami Herald: “Overtown School Regains its Status Glory after 32 Years”, August 8, 1999.

Miami Herald: “Booker T Washington Returns to its Academic Roots”, August 31, 1999.

Images:

Cover: Booker T Washington High School on February 15, 1930. Courtesy of the Florida State Archives. Photographer: William Fishbaugh.

Figure 1: Front page of Miami Tribune on Tuesday, March 2, 1926. Courtesy of Miami Tribune.

Figure 2: Headline in Miami Daily News on Monday, June 28, 1926. Courtesy of the Miami News.

Figure 3: Photo published in the Miami Herald on July 7, 1926, of the support beam that failed causing the collapse. Courtesy of the Miami Herald.

Figure 4: Story in Miami Daily News on October 16, 1926. Courtesy of Miami News.

Figure 5: Portrait of Booker T Washington. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

Figure 6: Booker T Washington High School in 1927. Courtesy of Miami-Dade Library, Romer Collection.

Figure 7: Booker T Washington Second Graduation Class of 1929. Courtesy of the Miami Herald.

Figure 8: Demolition of Original Booker T Washington School on November 12, 1989. Courtesy of the Miami Herald.

Thank you. Please aside from Dunns works are there other books about Black Miami?why did the new CVS TARGET on 6th street use the name Sawyer Walk?