Friendship Garden & Civic Club

The story of the civic organization that fought for the rights of the residents of Overtown during the mid-1930s. This group was successful in getting the first library branch for the black community.

When the Friendship Garden Club was formed in March of 1936, its mission was to benefit the black community through the beautification of the grounds of the hospital, schools, and other green space in the segregated neighborhood of Overtown. The organization was founded by the wife of a reverend and other women who were interested in serving and improving South Florida neighborhoods. The group was one of the first racially integrated organizations in Miami and provided an example of how a group of civic minded altruists can make a difference in a community.

The club would go beyond the beautification projects by advocating for a public library, a police precinct, and other initiatives to benefit the residents of Overtown. As the scope of advocacy evolved, so did the name of the organization a year after formation when the group changed its name to the Friendship Garden & Civic Club. This is the story of the founding of the club and its principal founder, Annie Coleman.

Southside Colored Town

Born in Quitman, Georgia, on September 19, 1894, two years prior to the incorporation of the City of Miami, Annie M. Coleman, a graduate of Paine College in Augusta, Georgia, was a young widow with a small son when she met Reverend James Coleman, who was himself widowed with seven children. The two got married shortly before the reverend was offered a job to become the pastor of Saint Marks Baptist Church in Miami. The church was located in a section of today’s Little Havana neighborhood that was referred to as Southside Colored Town during the first two decades of the Twentieth Century.

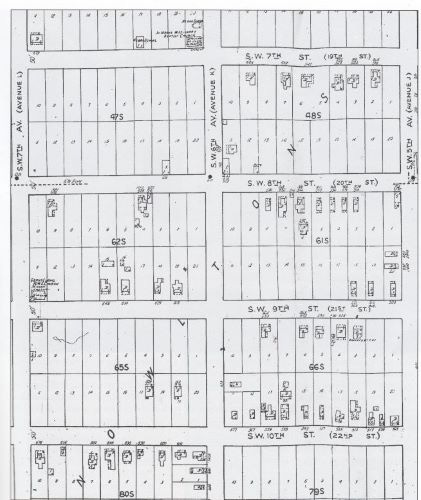

The segregated black section of Southside was located from SW Seventh Street to SW Tenth Street from north to south, and SW Fifth Avenue to SW Seventh Avenue from east to west. Southside Colored Town, also referred to as Black Southside, consisted of lots configured by Mary Brickell that were either rented or sold to black working-class families.

The Brickell family constructed a few small homes as rental property within this subdivision, but sold many of the lots to working-class black families who would construct what were characterized as small Bahamian shotgun cottages. In some cases, Mary Brickell was both seller and lender for properties sold to families in this section for it was difficult, if not impossible, for black families to qualify for a bank mortgage during the Jim Crowe era of Miami.

Many of the lots sold in this quarter were to Bahamian laborers who worked for the Brickell family to help construct homes, streets, and other infrastructure in the Brickell neighborhood. In July of 1907, Mary donated one of the lots for a school which was constructed by the school district and referred to as the ‘Southside Colored School’ when it was completed in July of 1907.

Mary was held in such high esteem by the black community in Miami that upon her death in 1922, a group of black community leaders published a remembrance in the Miami Herald where they expressed their feelings about the departed matriarch of the Brickell family:

“The death of Mrs. Mary Brickell, though to be expected in the course of nature, is a distinct loss to this section of Florida and particularly to the colored people of Miami, whom she helped in every practical way to become not only property holders, but better citizens.”

Southside Colored Town consisted of a grocery store, a school, and two churches, Grant Chapel AME Church, and Saint Marks Baptist Church. It was the latter church that hired Reverend Coleman to become their pastor in 1922. Saint Marks was located on the northwest corner of SW Seventh Street and SW Sixth Avenue, and the school was built three lots to the west of the church. The Grant Chapel AME Church was located on the corner of SW Ninth Street and SW Seventh Avenue.

Prior to the Colemans moving to Miami in 1922, growth of the city began to force black families out of Southside Colored Town and compelled them to move north to the segregated community referred to as Colored Town, or what many in the black community referred to as ‘Overtown’. This process began as early as the late 1910s which is confirmed by an article in the Miami Metropolis published on April 18, 1918, which carried the headline: ‘South Side Colored Town Being Gradually Weeded Out to North’. The piece explained the removal process as follows:

“A movement is said to be on foot by property owners to gradually move the houses from south side colored town to north side colored town (Overtown). It is stated that a number of houses have already been moved to the colored town north as part of this process of gradual transformation. With the extension of white population on the north side (of Southside Colored Town), there are now white people living not only to the north of the (Southside) colored district but in the district itself and the land is becoming too valuable for the class of residences that are located there.”

The City of Miami’s new charter implemented in 1921 formalized racial segregation of neighborhoods by providing the city the power “to establish and set apart districts for white and negro residents.” This change in the city’s authority accelerated the consolidation of black neighborhoods into Overtown. South Side Colored Town was not the first nor the last black neighborhood in Miami to experience forced removal to Overtown.

Move to Overtown

According to the Miami City Directory in 1923, the Colemans lived at 542 SW Seventh Street, across the street and to the east from the Saint Marks Baptist Church. By the summer of 1924, the church purchased property in Overtown at 324 NW Sixteenth Street, where they would construct a church. Although the completion date of the church is not clear, the congregation filed for a permit to construct a reinforced concrete baptism pool in October of 1927. Reverend Coleman most likely spent a fair amount of time facilitating the move from Southside to Overtown during his first few years as the pastor.

In addition to the move of the church, the Colemans purchased a home at 2057 NW Sixth Court completing the family’s relocation to Overtown. When the Colemans moved to the neighborhood, Overtown had no paved streets, parks, or a library, which inspired Annie to get involved in her new district to help fight for what other communities in Miami took for granted.

On June 22, 1923, Annie Coleman became a charter member of an organization called the Y-Club which was formed by Julia Jenkins Baylor. In addition to her work as a teacher, music instructor, and secretary during her early years in Miami, Annie wanted to make a positive impact on her community through civic engagement. The Y-Club was the forerunner of what would become the Murrell Branch of the YWCA. Annie would continue making an impact in Overtown with the formation of the Friendship Garden Club in 1936.

Formation of the Club in 1936

When Annie Coleman, along with several other women including Naomi Espy and Frances Levkoff, saw the opportunity to improve the appearance of Overtown through the addition of gardens and the upkeep of landscapes in public spaces, she formed the Friendship Garden Club on March 15, 1936. The original mission of the club was to clean-up and beautify the grounds of the Christian Hospital, Booker T Washington High School, Dunbar Elementary, as well as other grounds of institutions within the neighborhood.

Around the time of the formation of the garden club, Annie met several white women from the Trinity Methodist Church, who were also prominent members and officers of the Miami Woman’s Club. Alice Guyton, Mary Reeder, and Maud Feaster partnered with the members of the Friendship Garden Club to help support their mission. The three women were the wives of prominent businessmen who held a lot of influence within the City of Miami. J Avery Guyton and Jerome Feaster were executives and board members of the Belcher Oil Company, and Clifford Reeder was a two-time mayor of Miami from 1929 – 1931, and then again during the war years from 1941 – 1943.

Each of the three woman developed a special friendship with Annie Coleman and did what they could to help the Overtown community, supporting the initiatives of the Friendship Club. In what was controversial for the time, Alice Guyton worked with Annie to book a quartet of black singers to perform at the Miami Woman’s Club in 1937. Those in power in Miami opposed the idea of black singers performing in an all-white venue. However, the opposition to the performance not only increased Alice’s resolve to schedule the performance, but also inspired her to arrange for the singer’s transportation by sending a car service to pick up the quartet from Annie Coleman’s home in Overtown to bring them to the Woman’s Club located at 1737 North Bayshore Drive. While the police sat outside the venue during the recital, they did not intervene, and the show proceeded as planned.

A year after the formation of the club, its members felt that the mission as a garden club was too limited for what they wanted to accomplish within the Overtown community. Shortly after formation, the club’s name was modified to the Friendship Garden and Civic Club, and their first order of business was to establish a library within the neighborhood.

Dunbar Library Branch in 1938

Prior to seeking an official branch of the Miami Public Library, Annie Coleman offered a vacant grocery store building on her property to serve as the first library. Books were donated by community members and the Miami Woman’s Club which allowed the vacant building to open as the Dunbar Library in 1936. While the use of the former grocery store as a library was considered a temporary solution, the club began an initiative to pursue a formal library branch supported by the Miami Public Library system.

By the fall of 1937, the members of the club, with the support of Guyton, Reeder, and Feaster, the Friendship Garden and Civic Club began petitioning the City of Miami for an official branch. Annie and Naomi Espy led the fundraising and advocacy campaign to obtain an official library branch within the Overtown community.

At first, the club members identified a plot of land at NW Fourth Avenue and NW Eleventh Street, which was occupied as the dog pound at the time, as a potential location for the new library branch. This location would have been ideal given its proximity to Booker T. Washington High School. While the club was identifying and recommending locations, they were also seeking monetary and book donations for the existing library to keep it open while pursuing a city operated library branch.

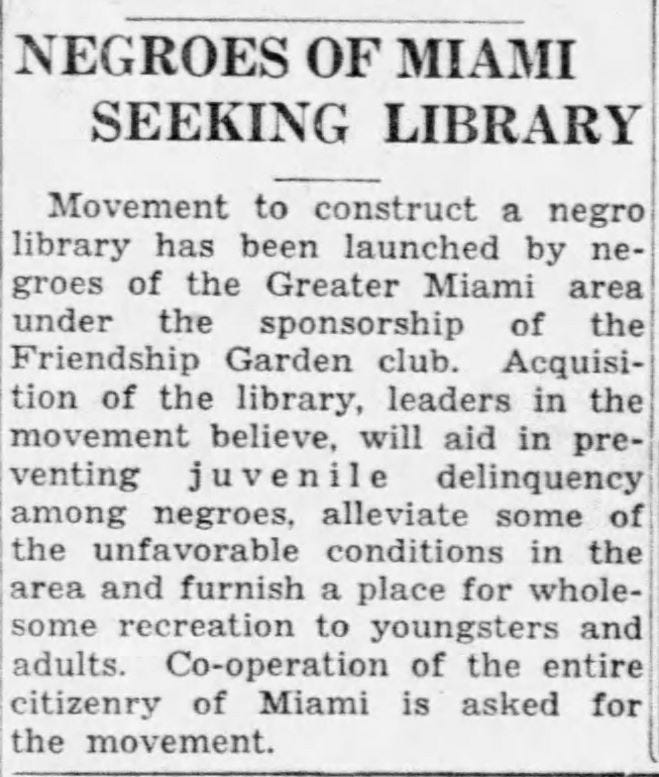

An article in the Miami News on November 21, 1937, reported:

“Movement to construct a negro library has been launched by negroes of the Greater Miami area under the sponsorship of the Friendship Garden club. Acquisition of the library, leaders in the movement believe, will aid in preventing juvenile delinquency among negroes, alleviate some of the unfavorable conditions in the area and furnish a place for wholesome recreation to youngsters and adults. Co-operation of the entire citizenry of Miami is asked for the movement.”

In a Miami Herald article published on January 8, 1938, the Miami City Commission authorized the city manager to “grant, lease or sell tract (of land) for purpose” of erecting a library. Frances Levkoff, one of the founding members of the Friendship Garden and Civic Club, suggested the use of a city-owned lot at NW Third Avenue and Eleventh Street, and was quoted as saying that “the materials, funds, and books have been pledged for the proposed library building.”

Ultimately, the club was successful in the establishment of the Dunbar Branch of the Miami Public Library system. However, the community was not granted a new building and opened the Dunbar branch library on March 14, 1938, in the same building it had been operating in on the Coleman property since 1936. With the assistance of the Miami Woman’s Club, the official branch was outfitted with additional materials and books, and would continue to operate out of the former grocery store building until Dana A. Dorsey donated land for a new library building in 1940.

Dorsey Memorial Library in 1941

Dana Albert Dorsey, who is often referred to as Miami’s first black millionaire, made his fortune buying and renting real estate. At one time, he owned an islet south of Government Cut that he sold to Carl Fisher, which we now refer to as Fisher Island. Dorsey was also a philanthropist who donated land for a park and school, as well as donated money for many causes to benefit the black community in Miami. On February 14, 1940, just fifteen days prior to his death, Dorsey donated land for a library at 100 NW Seventeenth Street in Overtown with the following deed covenant:

“That the grantee (Washington Heights Library Association), its successors or assignees, shall within eighteen months from the date of this conveyance erect upon said real property a building suitable for use as a public library and shall at all times keep and maintain said public library for the free use, benefit, education and enlightenment of the members of the Negro race.”

Given the short timeframe to erect a library building, Annie Coleman and other club members quickly got to work to raise money to help construct a new library building. The campaign raised $2,000 and the City of Miami contributed an additional $7,000 to provide enough funding to construct the library by the deadline set in the deed covenant. The building was designed by the prominent architectural firm of Paist and Steward and was completed in time for the library to open on August 13, 1941, as the Dorsey Memorial Library, named for the benefactor who provided the land.

The building served as the primary library branch in Overtown for twenty years, until the branch was closed in 1961. The masonry vernacular library building was historically designated and restored in 2003 and remains standing at 100 NW Seventeenth Street in Overtown today.

Black Police Precinct in 1944

Shortly after opening the Dunbar Library in the vacant grocery store in 1937, Annie Coleman would observe residents of the neighborhood playing dice when white police officers would break up the game and take the money of the participants. She noticed that the kids in the neighborhood were avoiding the library because of this activity. Annie felt that residents and the children of Overtown would be better served if the neighborhood was patrolled by black officers. This began a crusade that would take seven years to come to fruition with the hiring of black officers in 1944.

When Annie discussed this idea with her friends Mrs. Guyton, Reeder, and Feaster, they agreed to help advocate for black patrolmen to police Overtown. They suggested expanding the advocacy group to include some of the prominent black male leaders in the community. The group reached out to Captain James E. Scott, Father John E. Culmer, and Dr. I.P. Davis and all agreed to be a part of the movement for the establishment of a black police precinct in Overtown.

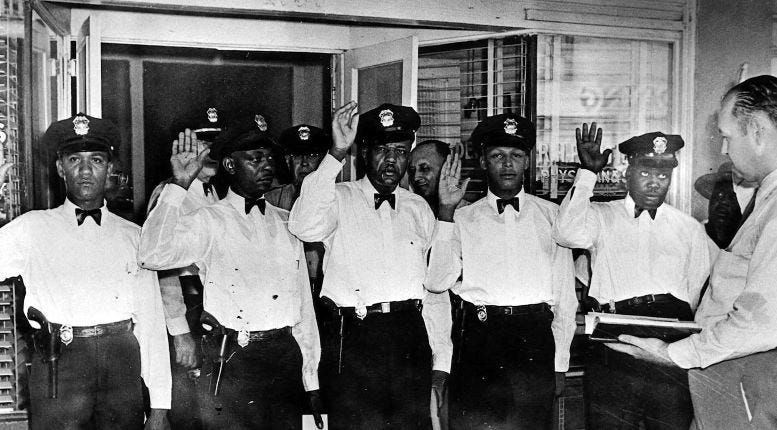

The group met at the Saint Agnes Parrish Hall in August of 1937 to plan their approach to petition the city leaders to have black officers patrol Overtown. There was a lot of resistance to the idea, which is why it took seven years, from 1937 to 1944, in order for the Miami Police Department to agree hire black policemen. On September 1, 1944, the first five black police officers were sworn into service.

For the first six years, the officers patrolled either on foot or by bicycle and would use a dental office as their precinct headquarters until one was established in May of 1950 at 480 NW Eleventh Street. The location of the precinct was a block west of the first location requested by the Friendship Garden and Civic Club for the first Dunbar Branch library building back in 1937, which was occupied by the dog pound at the time.

Legacy of Annie Coleman

Throughout her life, Annie Coleman never shied away from civic engagement. The Friendship Garden and Civic Club provided her and the other members of the club with the platform to provide positive change for the black community during difficult times. The organization raised money for the Christian Hospital, Miami’s only black hospital during segregation, and collaborated across racial lines to collaborate with civic minded women to improve the lives of the residents of Overtown. There may not have been a public library or proper law enforcement to serve the black community if it were not for the Friendship Garden and Civic Club.

For all of her contributions, Annie Coleman was recognized as a community leader throughout Miami. She was awarded the city’s Silver Cup award in 1942 for outstanding civic contributions. She was one of three black leaders asked to speak during the dedication of the first addition of the Liberty Square housing project. The other two were Reverend John Culmer and Dana A. Dorsey.

When the first lady, Eleanor Roosevelt, and accomplished opera singer, Marian Anderson, visited Miami, Annie Coleman was asked to lead the greeting party. In 1966, the Miami Housing Authority dedicated a 144-unit complex in her name. The Annie M Coleman Gardens at 2501 NW 56th Terrace was built to house families displaced by the construction of the I-95 expressway. Two years earlier, despite all she accomplished in the Overtown neighborhood, Annie was also displaced from her home of forty years for the same reason.

Annie Coleman outlived all of the people she collaborated with to form the Friendship Garden and Civic Club. Her husband passed away in August of 1958, and almost all of her friends and colleagues associated with the club preceded her in death when she passed away on August 19, 1981, at the age of 86. She lived a full life of achievement and overcame a lot of headwinds to accomplish what she did during her time in Miami.

Resources:

Website: “Y Club History”, The Black Archives.

Website: “Dorsey Memorial Library”

Website: “History of Black Police Precinct”, Black Precinct and Courthouse Museum

Miami Metropolis: “Southside Colored Town Being Gradually Weeded Out to North”, April 18, 1918.

Miami Daily News: “Digest of the New Miami City Charter”, July 28, 1921.

Miami Herald: “Colored People Mourn Mrs. Brickell’s Passing”, January 14, 1922.

Miami Herald: “Public Library Site in Negro Area Asked”, October 29, 1937.

Miami News: “Negroes of Miami Seeking Library”, November 21, 1937.

Miami Herald: “Club Sponsoring Library Campaign”, November 29, 1937.

Miami Herald: “Commission Favors Negro Library Site”, January 8, 1938.

Miami News: “Colorful Past of Miami Woman’s Club Recalled”, January 22, 1939.

Miami Herald: “Ground to be Broken for Housing Project”, July 18, 1939.

Miami News: “Miami Negro News”, January 23, 1952.

Miami Herald: “Annie Knows the Meaning of Relocation”, by Martha Ingle on June 6, 1966.

Miami Herald: “She Helped Pave the Streets and Pave the Way”, by Bea L. Hines on April 21, 1975.

Miami Herald: “Black Pioneers – Living Roots”, by Louise Montgomery on January 30, 1977.

Miami Herald: “Annie Coleman, black leader founded library”, Obituary, August 21, 1981.

Miami Herald: “Profiles in Black History”, by Beverlye Rao on February 15, 2006.

Miami Herald: “Friendship Club Donates Prom Dresses”, Dorothy Jenkins Fields on May 15, 2011.

Images:

Cover: Meeting of Friendship Garden Club in Saint Agnes Parrish Hall in August of 1937. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 1: Map of segregated black section of Southside in 1920. Courtesy of Larry Wiggins.

Figure 2: Annie Coleman outside her home at 2057 NW Sixth Court in Overtown in 1945. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 3: Article in the Miami News on November 21, 1937. Courtesy of Miami News.

Figure 4: Dorsey Memorial Library in the 1940s. Courtesy of Miami-Dade Public Library, Romer Collection.

Figure 5: Swearing in of first black police officers on September 1, 1944. Courtesy of Black Precinct and Courthouse Museum.

Figure 6: Portrait of Annie Coleman in 1935. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.