History of Miami City Cemetery – Part 2 of 2

Part two of the two-part series on the history of the Miami City Cemetery.

The Miami City Cemetery contains many interesting sections. A Catholic section lies near the front of the northern half of the graveyard and contains the remains of many members of Gesu Catholic Church, known earlier as the Church of the Holy Name. These parishioners bought burial plots adjacent to one another around the beginning of the 1900s.

In 1915, members of Miami’s first synagogue, Binai Zion, later known as Beth David, bought several contiguous lots near the rear of the graveyard. In its northern half, the synagogue erected a wall around the plots and secured the consecration of the area within by a rabbi.

The cemetery also contains black and white indigent sections and an American Legion section. The latter section is comprised of men who served this nation in wartime and consists of a Spanish-American War veterans’ burial area and two parallel rows of servicemen's graves within its lengthy northern and southern borders.

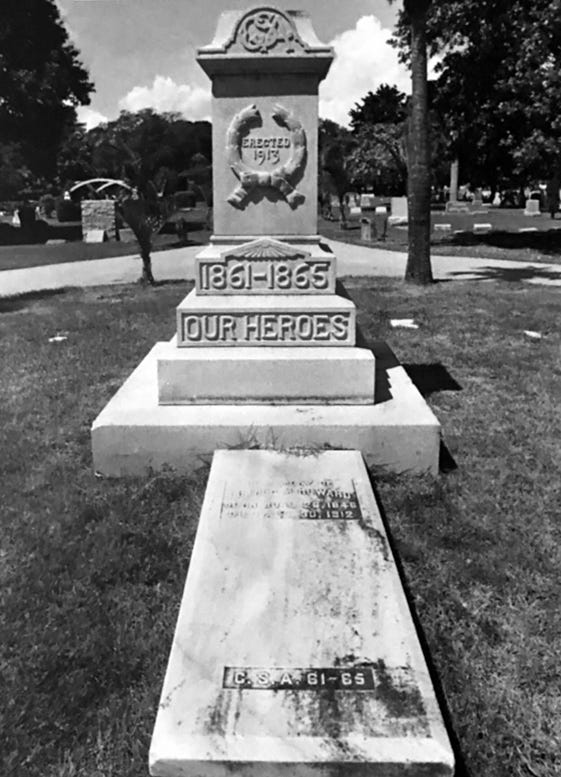

The cemetery also offers a Confederate Memorial Circle containing the remains of nearly twenty Confederate Civil War veterans. (Other Confederate veterans are buried elsewhere in the graveyard.) Standing near the front of the circle is a truncated monument to the Confederacy that stood, during an earlier era, in front of the old county courthouse. Its top segment, which reached two stories in height, was destroyed in the 1926 hurricane. This monument was typical of those found in southern cities in the years and decades following the conclusion of the Civil War. Located on Central Avenue, it stands about one hundred yards west of a circle of similar dimensions awarded to the Tuttle family in honor of Julia Tuttle, the “Mother of Miami,” who was buried there in 1898.

Since Miami was a deeply segregated city from its inception until the 1960s, the graveyard contains a separate black burial area. A significant percentage of these burials are of Bahamian background. Many of Miami’s most prominent African Americans are also interred there. Their ranks include R.E.S. Toomey, the city’s first black attorney, Reverend Theodore Gibson, its preeminent civil rights leader and Alex Lightbourne, an informed voice at the incorporation election in July 1896.

Several imposing mausoleums represent other prominent features of the memorial park. The largest of these was built by the oil-rich Belcher family. The structure contains burial places for thirty-two persons. Noteworthy are the Burdine and Budge mausoleums. Like the Belcher mausoleum, these two have lost their original, ornate doors to vandals.

Additional interesting elements of the cemetery include gravesites marked by masonry replicas of cut logs, emblematic of membership in the Woodmen of the World, an international burial association. Many tombstones are obelisk in design, and while there is no dominating architectural style in this burial ground, a late Victorian-era influence is noticeable.

The Miami City Cemetery’s first recorded interment is that of Henry Branscombe, an Englishman and entrepreneur, who died in his mid-20s of tuberculosis, a fatal malady in that era. Branscombe’s burial site is near the southeastern edge of the cemetery. It is marked by a Christian cross.

Since the burial of Branscombe, nearly 9,000 other persons have been interred in the cemetery. Their ranks include many prominent early Miamians including pioneers like William Wagner, one of the earliest 19th century homesteader, Dr. James M. Jackson, the young municipality’s first physician, and Joseph A. McDonald, Henry Flagler’s top lieutenant and the person who oversaw the incorporation of the City of Miami.

The graveyard offers many “firsts”. It contains the remains of the first mayor, John Reilly, first police chief, Frank Hardee, first banker, William Mack Brown, first hardware store operator, Frank Budge, and first black judge, Lawson Thomas. It is also the final resting place for one of the first department store owners, William Burdine, one of the earlier sheriffs, William Mettair, an early baker, John Seybold, and city marshal, John Frohock.

Numerous mayors are interred there, as are two members of “royalty” including the tomato and pineapple “kings” of Dade County, Tom Peters and T.V. Moore, respectively. This memorial park is also the final resting place for Jack Tigertail, an imposing Miccousukee leader, who was a homicide victim in the early 1920s.

The cemetery is filled with the remains of others who quietly contributed to the development of the Magic City. Internees represent communities as far south as Homestead and north as far as Ojus, near the county line.

Until the end of the 20th century, the cemetery was regularly victimized by vandalism. These disheartening incidents have diminished sharply in recent decades, assisted by a tall security fence, overhead lights, and a renewed interest in the cemetery. The once-forlorn area around the burial place is booming with new, upscale residential towers and commercial enterprises as gentrification continues to transform the adjacent center city neighborhood.

Even more important, perhaps, is the growing appreciation for the rich history of the graveyard. TREEmendous Miami, Dade Heritage Trust, HistoryMiami Museum and other institutions and organizations have assisted immeasurably in upgrading the appearance of the Miami City Cemetery. Periodically, scores of people turn out to plant shade trees in the graveyard, often under the auspices of TREEmendous Miami.

For two decades, Dade Heritage Trust, a prominent preservation group, held its annual Dade Heritage Days’ Commemorative Service in the cemetery on a Sunday in April. The highlight of this event was the unveiling of a tombstone by the grave of an African American internee, containing his/her name while often listing a chief accomplishment. For more than thirty years, HistoryMiami Museum has conducted detailed history tours of the graveyard. The institution’s highly popular Halloween tour has become a prominent community event.

These efforts and others represent the rich residue of love that many Miamians hold for this historic burial place. The above groups and individuals, like Ronnie Hurwitz and the late Penny Lambeth, continue their efforts to maintain this botanical park as a place where citizens can honor the dead, the deceased can rest in peace and visitors can gather to appreciate the past amid an ambiance of tradition and beauty.

Images:

Cover: Miami City Cemetery in 1974. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

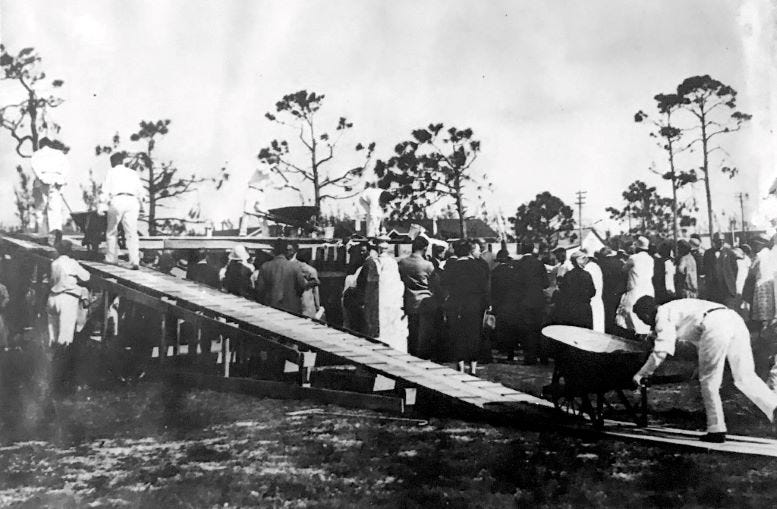

Figure 1: Combs Funeral home building Mausoleum in 1917 at Miami City Cemetery. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 2: Confederate Monument in October of 1986. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 3: Burdine Mausoleum in October of 1986. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 4: Miami City Cemetery in October of 1986. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.