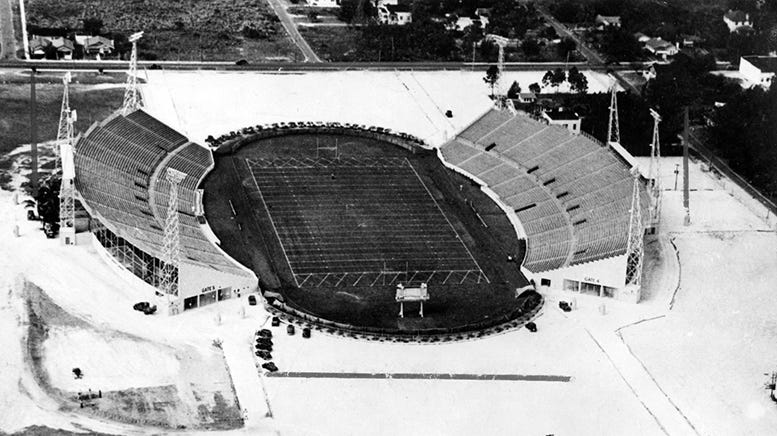

Orange Bowl Stadium (1937 – 1947)

Story of the first decade of the Orange Bowl Stadium in Miami, Florida, from 1937 until 1947. The stadium was dedicated to Roddy Burdine in 1937, but was officially renamed to the Orange Bowl in 1949.

Miami’s Orange Bowl stadium was the most revered sports venue in the City of Miami for more than 70 years. The inception of the stadium and the signature New Year’s Day game that was played in that stadium was inspired by the love of football and the need for tourism. The idea of the game was to encourage fans of the top football programs to travel to Miami to play in a warm weather climate during the worst part of winter for much of the nation. This would provide a reason for tourists to spend their limited travel budget during the Great Depression on a trip to the Magic City to root their favorite team to victory.

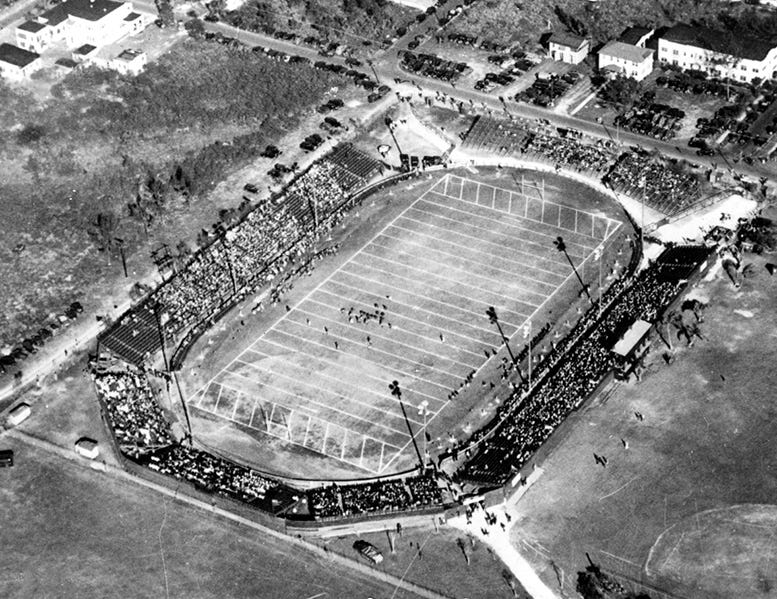

Although the venue was not originally named for the football game, it was so tightly linked with the event that it did not take long before everyone just referred to it as the ‘Orange Bowl Stadium’. From the very first game, the venue became a shrine for football and some of South Florida’s biggest events. Interest in acquiring tickets for the big New Year’s Day game grew exponentially through the years. This put pressure on city and Orange Bowl officials to continually modernize and grow the seating capacity of the stadium. Miami’s iconic football shrine could not afford to fall behind the size and features of other stadiums for fear of losing the right to host the best matchups during college bowl season each year. The Orange Bowl being relegated to a second-tier post-season game would have serious financial implications for the city’s pivotal tourism industry.

The first ten years of the stadium represented a decade of heavy use, enlargement, and reconfiguration to accommodate the growing popularity of the sport of football. The stadium advisory and Orange Bowl committees, as well as city officials, were constantly planning the next expansion and renovation of venue. Planning for the next renovation and enlargement was continuous. This is the story of the stadium’s first decade.

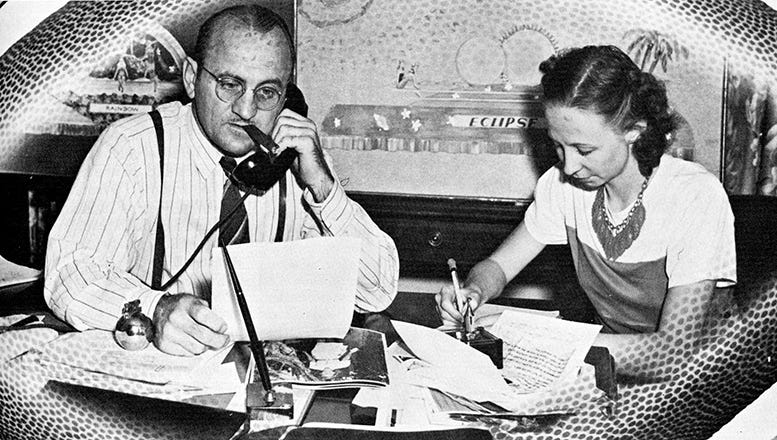

The Mad Genius – Earnie Seiler

South Florida has been the home to some creative boosters who could give a master class in how to promote an idea. Carl Fisher convinced the world that Miami Beach was “America’s Winter Playground” in the 1920s as it was being developed from a barrier island to what would eventually conform to the vision he was selling. Bill Veeck was a pioneer baseball innovator who applied his creativity to make minor league baseball popular in South Florida at the former Miami Stadium. However, the one man who stood the test of time in providing creativity to the Orange Bowl game and stadium, decade after decade, was Earnie Seiler, nicknamed the ‘Mad Genius’ by Miami Herald columnist Jimmy Burns.

Earnie was no stranger to the game of football. His involvement with the game dated back to the 1920s when he was the head coach for the football program of Miami High School. At that time, the team played on what Seiler referred to as a “sandspur field” at Royal Palm Park, which was located between today’s Biscayne Boulevard and SE Third Avenue, just south of Flagler Street. It was on this field that Seiler made a humorous blunder that he shared in an interview which aired on WQAM in 1973.

In that interview, Earnie shared the following story:

“It happened when I was coaching at Miami High in 1925. In those days, a coach couldn’t send a substitute player into the game with a play. The substitute player couldn’t say a word when he got into the huddle. So, I set up three buckets on the sideline. If I kicked down one bucket, it meant that I wanted the play to go off right tackle. Another bucket meant left tackle. Anyway, we were marching down the field like wild this day, we got down to our opponent’s 20-yard line, and in the excitement, I (accidently) kicked over the middle bucket. I didn’t notice it, but my quarterback did. I had told our quarterback to punt whenever he saw that I had kicked over the middle bucket. Well, this kid punted from the 20-yard line, kicked the ball into the street, and through the window of the old Calumet Building. We couldn’t get the ball out of the building, so we had to hold up the game until we found another football.”

Seiler was so synonymous with the venue that the Orange Bowl was called “the stadium that Earnie built” by the author of the book ‘Fifty Years on the Fifty: The Orange Bowl Story.’ It was Earnie Seiler who convinced the Public Works Administration (PWA), one of FDR’s depression-era alphabet soup agencies responsible for funding worthy municipal projects around the country, to commit to help fund the initiative to construct the first version of the Orange Bowl in 1937. He was also responsible for conceiving and organizing the Orange Bowl Parade before the game, and the halftime show during the game. Some of the halftime extravaganzas were just as captivating as the game itself.

A great example of how creative and committed he was to the Orange Bowl occurred in 1939. Seiler convinced undefeated Oklahoma to accept half the money offered by the Sugar and Cotton bowl games by sneaking on campus at Norman after they won their final game to remain undefeated, and writing ‘ON TO MIAMI!’ in chalk on the sidewalks and then selling the Sooner players on why the Orange Bowl was best for them with a morning lecture that featured huge posters of beautiful women in swimwear on the sands of Miami Beach. After the team accepted the offer, Earnie was quoted as saying “I’m a great believer in visual aids.”

Seiler was not only a co-founder of the Orange Bowl game and a catalyst for the construction of the original stadium, but he also remained a consistent presence on the Orange Bowl Committee, serving as executive director until 1974, and became the game and stadium’s most ardent advocate. When he felt the venue was falling behind the seating capacity and quality of other big game stadiums, he would push the city to invest in the Orange Bowl. He was not only the Orange Bowl’s most animated booster, but he was also the game and stadium’s caretaker.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.