Spanish Missions on Miami River – Part 1 of 2

Part one of a two-part series on the Spanish Mission periods along the Miami River.

The rich history of Greater Miami reaches back at least 10,000 years, or for nearly 350 generations, if we employ the old benchmark of thirty years as constituting a generation. Our awareness of the presence of these early people is based on several stunning archaeological excavations over the past thirty-five to forty years. However, we can also draw on documentary materials to help us understand the people who preceded modern-day Miamians. Such is the case with three Spanish missions that graced the north bank of the Miami River in the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries.

Spain opened the “New World” to European exploration in the aftermath of Christopher Columbus’ four voyages to the West Indies. They parlayed these voyages into a colonization campaign that swept La Florida, so named by Juan Ponce de Leon, into its colonial empire. The Spanish leader in Florida, Pedro Menendez, had manifold objectives in colonizing the area, including a determination to convert the native populations to Roman Catholicism through an ambitious mission system stretching from today’s South Carolina to and throughout the Florida peninsula.

As part of this effort, Menendez reconnoitered prospective sites before arriving at the mouth of the Miami River in 1566 where he was greeted by indigenous people named Tequesta by Ponce de Leon. A devout Catholic, Menendez chose the heavily populated area on the north bank of the river to open a fort and mission outpost in 1567.

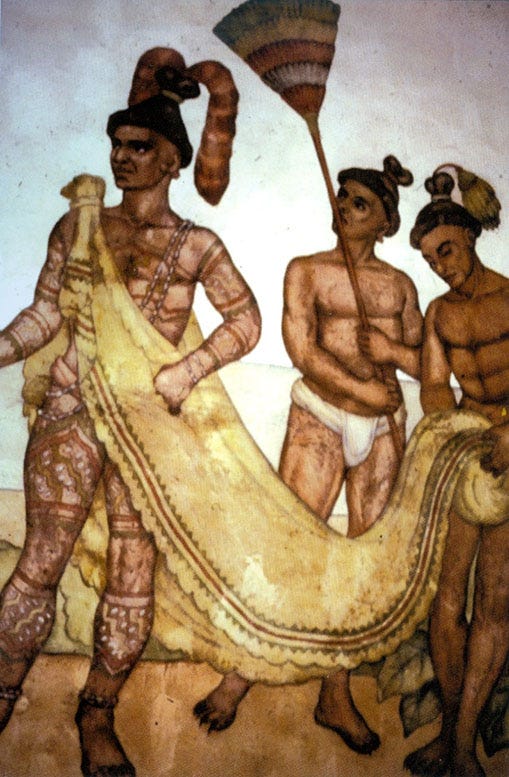

The Tequestas that Menendez met near the mouth of the Miami River had been living in a broad region stretching from Cape Sable, at the tip of the Florida peninsula, through today’s Broward County for at least three thousand years. Hunters and fishermen, but not agriculturalists, the Tequestas lived a seemingly idyllic lifestyle in a subtropical Eden.

They were closely allied to the Calusa tribe which inhabited parts of southwest Florida. Estimates on the number of Tequestas are, at best, an exercise in approximation. However, recent archaeological discoveries on the north bank of the Miami River indicate that many thousands lived in that area. Most estimates of the native American population of the future state of Florida, at the time of Spanish contact in the sixteenth century, estimate the figure at around 300,000.

The Spanish devised a mission system to civilize the native population. Missionaries labored to baptize the Indians and train them in the rudiments of a “civilized” life. Many gave their lives in the service of the Lord. In the 1550s, the Tocobago Indians, who lived near the shores of Tampa Bay, killed the Dominican Father Luis Cancer de Barbastro.

In 1565, Menendez established, with the help of four diocesan priests, the first permanent Indian mission, Nombre de Dios, which was located near the Matanzas River in St. Augustine. Diocesan priests began immediately preaching Christianity to the natives and did so until the Jesuit order of priests and brothers arrived a year later.

The group most responsible for the “Christianization” of native populations were the Jesuits, formally known as the Society of Jesus, a religious order founded by St. Ignatius of Loyola in 1540. A Spanish courtier and part-time soldier, Ignatius underwent a conversion after sustaining a debilitating leg wound in one of the dynastic wars of that time. The entry of the Jesuits can be traced to Menendez’s royal asiento (a license issued by the Spanish to bring, in this case, Christianity to La Florida), which charged him with the responsibility for converting the Indians within his lands to “Our Holy Catholic Faith.”

Menendez turned to the nascent Jesuit order for assistance. On October 1, 1565, Menendez petitioned the Society of Jesus in Spain for additional missionaries to the Indians who were friendly and receptive to the diocesan priests. Menendez assured Father Diego de Avellaneda, S.J., the Jesuit provincial in Andalusia, and the person who oversaw the order’s activities in the Americas, that while he awaited the arrival of the Jesuits, he would extend every kindness to the Indians to make them more receptive to the new priests upon their arrival.

In 1565, and then later in 1566, Menendez journeyed along coastal Florida, erecting crosses and commanding Spanish soldiers to instruct the natives in the rudiments of Christianity. The Spanish monarchy, whose leader at the time was Phillips II, dispatched a cedula (a certificate or document) on March 3, 1566, to the leader of the Society of Jesus requesting that members of the order be assigned to Florida. Father Francis Borgia, S.J, the Father-General, or leader, of the Jesuits, complied and assigned three men to Florida

Through the summer, however, no Jesuits had appeared, testing the patience of Menendez, who complained in a letter written in September 1566 to the Jesuit Provincial of Andalusia, that “I had told them ( the Indians) that these religious (the Society of Jesus) were coming on the next ships and would soon talk with them and instruct them into becoming Christians; now, as no religious came, the natives think that I am a liar; and some of them have become angry and accuse me of deceiving them.”

However, on June 28, 1566, three Jesuit missionaries did sail from Spain to Florida. Divine Providence must have guided and cared for them, since the Atlantic Ocean, at that time of the year, was treacherous due to hurricanes. After a stopover in Havana, the missionaries arrived on September 14, 1566, near the mouth of the St. Johns River. Father Pedro Martinez, S.J., one of the missionaries, lost his way after making landfall; his mangled body was found later, an apparent victim of a clubbing by natives. Rescued by Menendez, Father Juan Rogel, S.J., and Brother Francisco Villareal, S.J., the two surviving Jesuits, returned to Havana.

The second and final installment of the Spanish Missions on the Miami River will detail the history of the mission at Tequesta.

Images:

Cover: Juan Ponce de Leon.

Figure 1: Rendition of Ponce De Leon meeting with Calusas.

Figure 2: Portrait of Pedro Menendez de Aviles. Courtesy of Florida Memory.

Figure 3: Tequesta Indians in Everglades. Courtesy of Theodore Morris.

Figure 4: Tequesta Indians. Courtesy of PBC History Online.