The Aquarium – An Early Miami Beach Tourist Attraction

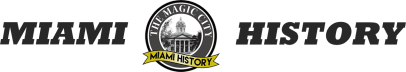

On January 1, 1920, Miami Beach pioneer James Allison opened the city's first tourist attraction and research center on Biscayne Bay, just north of the terminus of the County Causeway.

On March 26th in 2015, Miami Beach will be celebrating its centennial. During the celebration of 100 years since incorporation, Carl Fisher will be celebrated as the visionary and builder of early Miami Beach. While Fisher was not alone in building Miami Beach, he was the major driving force behind what Miami Beach became in the first half of the twentieth century.

Some of the other contributors to the building of Miami Beach were friends and business associates of Carl Fisher. One of those friends was James Allison, a business partner and friend of Fisher from Indianapolis, Indiana. This is the story of Allison’s vision for a tourist attraction and research center for South Florida’s marine ecosystem.

Presto-Lite Corp of Indianapolis

Carl Fisher was a man who never forgot his friends and colleagues. One of his friends was his business partner in building the Prest-O-Lite company, James Allison. Fisher owned one of the first automotive dealerships in the country and Allison had his hands in a number of businesses based upon family connections and his own personal innovations.

In 1904, the two men came together to form the ‘Concentrated Acetelyene Company’ which was to create and manufacture the first truly effective automobile headlight. The company was later renamed to Prest-O-Lite when a third business partner left the company in 1906. The lights were not based on electric power, but on acetelyene gas. Cadillac is credited with inventing the electric headlight in 1912.

Both Fisher and Allison had begun to amass a small fortune while building their company. However, it wasn’t until Union Carbide bought Prest-O-Lite in 1917 that both men became multi-millionaires. Fisher and Allison would go on to found a number of significant other ventures that live on today, including the Indianapolis 500 Speedway and the Lincoln Highway.

If both men chose to retire after their work in Indianapolis in the mid-1910s, no one would have blamed them. Together they had accomplished so much in a relatively short period of time.

Fisher Convinces Allison to Join Him in Miami Beach

It was Carl Fisher who decided to live part of his time in Miami. Since the arrival of Flagler’s first train in 1896, Miami had become a very chic destination for the wealthy industrialists of the day. After getting involved with helping John Collins with his bridge from Miami to what would become Miami Beach, the entrepreneur in Fisher couldn’t help but capitalize on the opportunity to build a world class destination resort in sunny South Florida.

Fisher had been in Miami since 1910, and he had big plans for Miami Beach with the land he got from both John Collins and the Lummus Brothers in exchange for his financial assistance. Fisher always thought big and he reached out to his former business partners to become involved with his vison for Miami Beach. All of his former associates turned him down, including James Allison.

Prior to the sale of Prest-O-Lite in 1917, Allison was in his mid-forties and contemplating retirement. His father and two brothers died in their 40s, and he had already suffered a heart attack at the age of 41. He was able to convince his wife to consider getting involved with Fisher’s dream of building Miami Beach into the “World’s Winter Playground”.

In February of 1916, Allison decided to come down and check out Fisher’s development of his grand vision. Although development was not far removed from its inception, Allison saw Fisher’s vision and was very enthusiastic. He decided to participate as a financier, at least initially.

The Flamingo Hotel

Fisher knew that the wealthy visitors to Miami Beach would require entertainment. He planned to provide polo matches, golf and speedboat races. By the late nineteen teens, Fisher’s vision was progressing nicely.

It was around the same time, the late nineteen teens, in which hotel rooms on Miami Beach were becoming very scarce. There were only a few places to stay on the beach including Fisher’s Lincoln Hotel, Browns Hotel, The Breakers and several apartment homes. In 1918, Allison’s residence was listed at the Lincoln Hotel. The 1920 census listed James Allison as a guest in the home of John Levi.

With such a scarcity of hotel rooms, Fisher and Allison began planning a grand hotel in the late 1910s. The hotel would be called The Flamingo, and it was designed to appeal to the wealthy. It was to be built on the bay side of Miami Beach and it was to be close to all of the activities: polo matches, golf and the speedboat races. Due to a lot of factors, the cost overruns escalated rapidly and Allison decided not to participate any further in the building of the Flamingo.

Allison Shifts His Attention to “The Aquarium”

Since his childhood, James Allison had always pictured himself sponsoring a collection of some of the finest fish in the world. He spent a lot of time sport fishing in Miami and he began to develop an interest in tropical sea life. By 1919, Allison began to envision starting a world class aquarium that would serve the dual purpose of providing a research facility to study tropical species and a tourist attraction to visitors of Miami Beach.

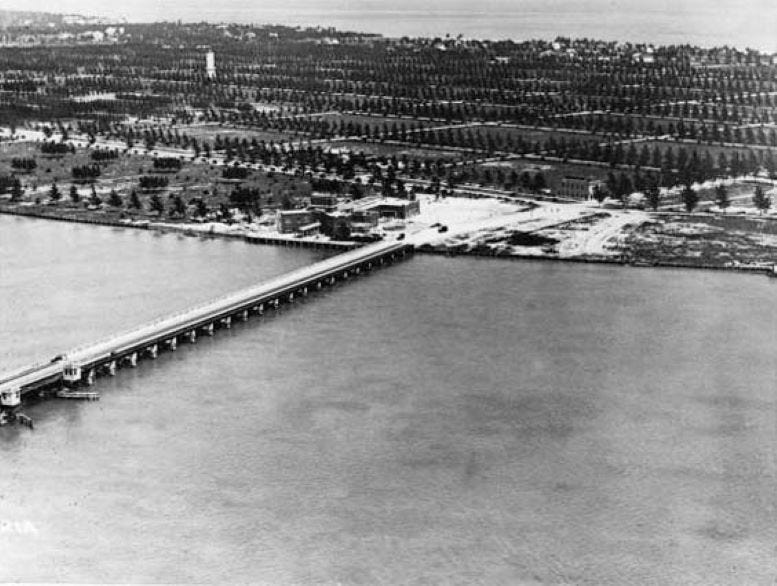

Allison pitched his idea to Fisher and to some Miami County Commissioners. Everyone was very excited about the possibility of providing a world class tourist destination on Miami Beach. There was talk about building the aquarium on the south side of the developing County Causeway (now the MacArthur Causeway).

The County Causeway was proposed, and partially funded, by the Lummus Brothers, in 1917. It was supposed to be fully funded and completed sooner, but the Causeway did not get completed until February 17th, 1920. The main delay in the completion of the bridge was the United States participation in World War I.

Allison favored a parcel of land that was just north of the causeway in order to capitalize on the traffic patterns expected once the County Causeway opened. Given the available activities of the day, he figured that traffic would go north and it was more likely that visitors would notice and stop at The Aquarium as they approached Miami Beach if it were located on the north side of the causeway.

James Allison had hoped that The Aquarium could be completed in time for the 1920 tourist season. Given his start time, his hope was very aggressive. He not only needed the facility designed and built, he would need to put together an advisory committee, hire a director and begin collecting tropical sea creatures for exhibit and study.

Allison’s friend, Jack La Gorce, recommended Louis L. Mowbray for the job of director of The Aquarium. Mobray had a fine reputation of building and running aquariums. He started and ran the Boston Aquarium and was assistant director of the New York Aquarium.

Allison was also able to convince a number of high profile men to join his advisory committee. Some of the dignitaries included Alexander Graham Bell, the president of the National Geographic Society, secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, the U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries, Carl Fisher and several other prominent and accomplished gentlemen.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.