The Soldier Poet of Florida

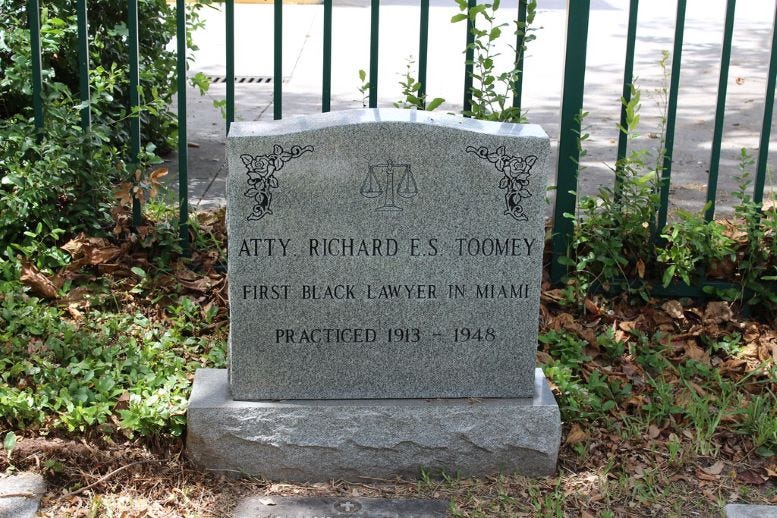

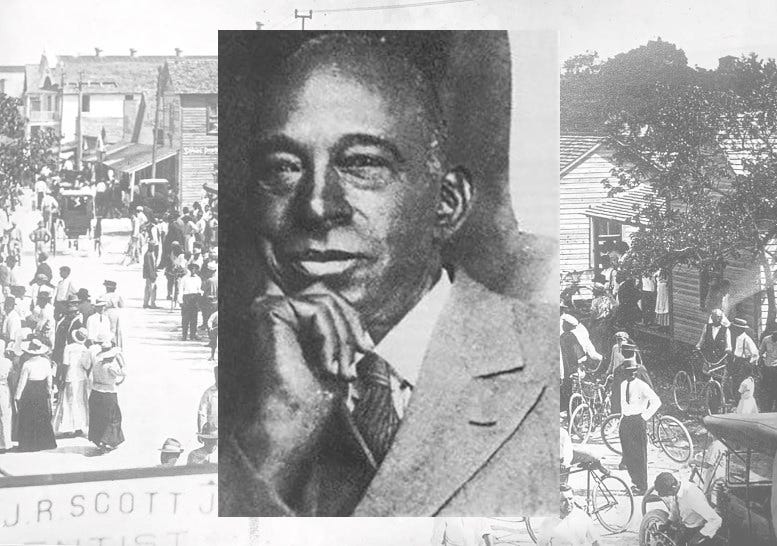

The story of Miami's first black attorney who moved to South Florida in 1913. He was a war veteran, poet, attorney and civic activist for the black community in early Miami.

Richard E.S. Toomey led a fascinating life at a time, and in a place, it was difficult for a black man to make a difference for his community. He was a soldier, poet, attorney, and civic activist who strived to provide positive and uplifting leadership for Miami’s black citizens during a time of segregation and Jim Crowe restrictions prevalent in Florida and throughout the southern United States.

Toomey’s early life accentuated his education and leadership abilities. He was commissioned to lead a regiment during the Spanish American war, wrote a book of poetry that he read at the Congressional Library, and attended law school at Howard University. Once he arrived in Miami, he provided legal services for the black community, and helped organize several important organizations to support and advance basic rights for the black citizens living and working in Miami.

Early Life

Richard was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to Henry and Lydia Toomey in May of 1862. Although his father worked with his hands as an oyster fisherman after the Civil war according to the 1870 census, Richard followed a different path and focused on developing his mind and getting a formal education. He earned his undergraduate degree from Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, and later graduated from Howard University Law School in 1906.

When the USS Maine was sunk in Havana Harbor and the Spanish American War broke out in 1898, Richard was working as employee for the federal government in Washington D.C. when he enlisted the U.S. Army. Richard got married, on September 27, 1888, several months prior to the outbreak of war, to Minnie D. Clem of Greenville, Tennessee. The couple would have three children together during their marriage.

In his obituary, it was written that President McKinley commissioned him to lead Company B of the 8th United States Volunteer Colored Infantry, then referred to as the “8th Immune Regiment” for the mistaken belief that black soldiers would be immune from tropical diseases they may encounter during combat in Cuba. In the same article, it was stated that his regiment was deployed to Cuba and saw action in the Battle of San Juan Hill. There is not a lot of detail of Toomey’s war record, but we do know that the Spanish American War was a short one. John Hay, U.S. Secretary of State in 1898, referred to the conflict as the ‘splendid little war’ because it only lasted for 100 days.

Following the war, Richard authored a book of poetry entitled ‘Thoughts for true Americans; a book of poems, dedicated to the lovers of American ideals’, which was published in November of 1901. He was given the rare opportunity to read his work at the Congressional Library on April 26, 1902, making him only the second black man to be given the opportunity to speak at the prestigious institution. The first was Paul Lawrence Dunbar who was considered one of the first influential black poets in American literature. During the reading, Toomey was joined by his brother, Louis Ellsworth, who played the piano during Richard’s recitation of his work.

Toomey developed a friendship with Dunbar who nicknamed Richard the ‘Soldier Poet’, a moniker that followed him for the remainder of his life. Following his reading at the Congressional Library, a Washington D.C. based newspaper, The Colored American, referred to Richard as the ‘Poet of the People.’ Once Toomey moved to Florida and became well known for his written work, people referred to him as the ‘Soldier Poet of Florida.’

R.E.S. Toomey, as he was often referred to in local Miami newspapers, incorporated a conflicted message in his writings. His poems were a mosaic of patriotic idealism combined with a commentary of how American ideals do not apply equally to all races. While his work conveyed optimism about the future of the country, he used poems to aspire for a better America. Given the conditions he had to navigate during his lifetime, especially in the south, his undaunting belief that America can do better and provide a bright future for all people was a theme that can be found in his writings.

On October 5, 1906, Toomey passed the Washington DC bar exam and was admitted to the district court to begin practicing law. For the next six plus years, Richard would sharpen his legal knowledge practicing law in DC and Baltimore, but would choose to move south to apply that knowledge in what would become his adopted new city where he would spend the rest of his life serving the black community through legal services and civic leadership.

Moved to Miami in 1913

Richard arrived in Miami in 1913 where he quickly became known for being the city’s first black attorney. Laws and living conditions were very different in Miami for black people than they were in either Baltimore or Washington DC at the time of Richard’s arrival. Despite being a successful professional, he was expected to live and work in a segregated neighborhood known as ‘Colored Town’ at the time.

Despite being fully credentialed to practice law in the State of Florida, Toomey had to represent his clients quite differently in Miami. He could not join the bar in Miami and therefore could not argue cases in a courtroom on behalf of his black clients. When a case went to court, he had to hire a white attorney to argue the judicial proceeding. Toomey could not interrogate witnesses or speak directly to the jury.

While Miami’s Jim Crowe sensibilities provided obstacles for Richard to practice law, he was resolute to fight for the rights of not only his clients, but the entire black community. He did not relocate to Miami to just build a law practice, but to make a difference for his community through leadership in a variety of endeavors.

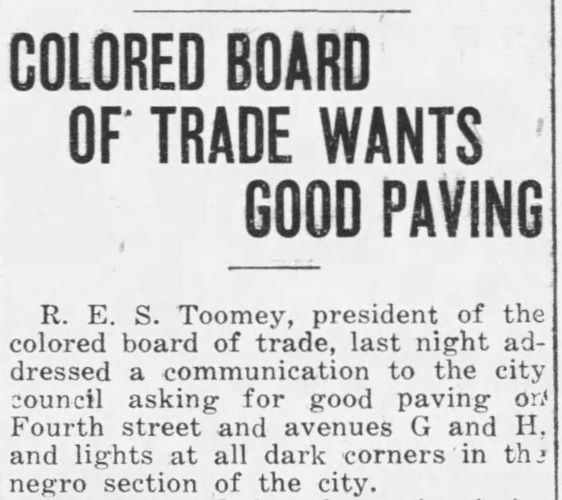

Colored Board of Trade in 1915

By 1915, the black population of Miami had become an economic force that could use a unified organization to advance their commercial interests. According to the article titled ‘Colored Town Section of the City of Miami is a Thriving Community’, published on October 16, 1915, in the Miami Daily Metropolis, there were approximately 7,000 black people in Dade County who had an aggregate real estate holding of $800,000, which is nearly $25 million in today’s dollars. In the same article, it was estimated that there were approximately 5,450 black people in the city of Miami, with an aggregate real estate and personal property value of $500,000, which is roughly $15.5 million in today’s dollars.

It was this acknowledgement of economic influence that led the business leaders in the black community to organize a board of trade. It was Kelsey Pharr, the recording secretary of the newly formed organization, who authored the aforementioned article where he outlined the need and aspirations for the civic and commercial association. In addition to Pharr, the other officers were Reverend J.T. Brown, president, Richard E.S. Toomey, managing secretary, and H.S. Bragg, merchant and president of the Miami Industrial Mutual Benefit and Savings association.

Pharr described the purpose of what was labeled by the association’s members as the ‘Colored Board of Trade’ as follows:

“It is the clearing house for the best ideas of the race along lines of commercial and civic betterment.”

The board not only fought for improvements in the community, such as better paving of the roads within Colored Town, but also advocated for better school facilities and reasonable policing within the community. Toomey was an early advocate for a black police precinct to patrol and provide law enforcement in the community. Too often, the white officers assigned to Colored Town were abusive and treated the black citizens unfairly. The idea of a black police precinct did not come to fruition until 1944.

The board also advocated for a new taxing district to relieve overcrowding of black segregated schools, honored black soldiers returning from war, organized community events and parades for special occasions in Colored Town, and encouraged and organized the community to vote during elections. Although it is not clear when the organization disbanded, the last mention of the ‘Colored Board of Trade’ in the two main newspapers of Miami was in June of 1926. Prior to that date, the organization was referred to often in both the Miami Daily News and the Miami Herald.

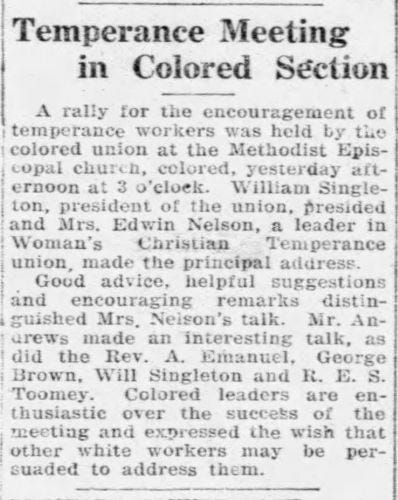

Temperance Movement

The year that Richard Toomey arrived in Miami, Dade County voted itself dry in October of 1913. Toomey saw the impact that alcohol had on Miami’s segregated black communities and soon became a leader in the local temperance movement. He developed alliances and friendships with leaders in both the black and white communities to fight to keep Dade County dry.

Because Miami was incorporated as a dry city in 1896, an area outside of the northern boundary of the city, referred to as North Miami, became a place for alcohol consumption, gambling and prostitution. When the owners of the property in and around North Miami, which is today’s Omni neighborhood, objected to the debauchery, Sheriff Dan Hardie shut down the illicit establishments which forced the red-light district to move to Colored Town, which became referred to as ‘Hardieville’ given the sheriff’s role in shutting down North Miami. Due to the racial dynamics of the time, and the behavior of the people who frequented ‘Hardieville’, life became untenable for the black residents of the area we know today as Overtown.

Upon Toomey’s arrival, he joined forces with leaders in the white community to ensure that the vote in October of 1913 did not get overturned. Edwin and Ida Nelson were vocal leaders in the temperance movement, and they would often help Richard, and other black leaders, fight to keep Dade County dry. Ultimately, through the efforts of temperance leaders such as Richard Toomey, Hardieville was shut down for good in 1917, and Dade County remained ‘dry’ until the end of national prohibition in 1933. While the manufacture, transport, and consumption of alcohol was illegal for twenty years (1913 – 1933), in Dade County, it was said that Miami was the leakiest place in America during the prohibition years, meaning that the law did not stop anyone who wanted to consume alcohol from doing so.

Negro Uplift Association – 1919 to 1920

In addition to Toomey being actively involved in local civic organizations, he also took time to help found a statewide organization in 1919 called the ‘Negro Uplift Association.’ The purpose of the group was to advocate for improvement of schools for black children, admission of Negroes to juries, and desegregation of public facilities such as railroad depot waiting rooms.

In May of 1919, Richard headed a delegation of black leaders from around the state to meet with state representatives in Tallahassee, Florida. The association leaders explained their reason for organizing and requested improvements in living conditions for their communities. The delegation listed four indispensable needs for their respective communities:

1. Adequate school facilities.

2. Absolute justice before the courts.

3. Humane treatment by officers of the law in making arrests and after the arrest is made.

4. Right so labor as free men.

Following the meeting, Toomey shared his thoughts:

“The officers of the state government gave serious and grave attention to the matters we presented and assured us that such matters that we asked to be taken up would receive immediate and earnest attention. The gentlemen were surprised that the colored citizens had assembled in this civic way and had unitedly given expression to their desires, hopes and requests. The feature which caused the most questioning and aroused the greatest interest was that which appertained to negro citizens, when qualified, being included in the jury system of the state.”

In June of 1919, the association sent a letter to Governor Sidney Johnston Catts regarding participation in jury duty and the governor assured them that he would “guard negro interests” when it comes to jury selection. However, despite the governor’s assurances, not much changed during the months following his promise.

As part of the Negro Uplift Association convention in Ocala in April of 1920, the board crafted a petition and organized a committee to present the petition to the Florida Legislature the next time they convened. When the committee’s representatives got the opportunity to present the petition and their list of suggestions, they were quickly interrupted and denied the opportunity to finish reading and submitting their petition in the record of legislative proceedings. From that point forward, the association was subsequently ignored by the legislature.

Like the Colored Board of Trade, it is not clear how long the Negro Uplift Association remained active. While there were consistent articles in the local Miami newspapers about the association in 1919 and early 1920, there was no mention of the Negro Uplift Association in the Daily News or Herald in the years following 1920.

Final Days at VA Hospital in Biltmore Hotel

Richard E.S. Toomey spent the last thirty-five years of his life in Miami fighting for his clients and his community. In the spring of 1948, Richard was 87 years old and began experiencing the effects of old age which required him to be hospitalized. Given his service during the Spanish American War, he was admitted to the Pratt Veterans Administration hospital in April of 1948.

The VA hospital was hosted in the Biltmore Hotel after it was converted to an army hospital during World War II. It was named the Pratt General Hospital during the war, but was transferred to the VA in May of 1947. The Veterans Administration operated out of the Biltmore until the Bruce W. Carter VA Medical Center opened in May of 1968 at 1201 NW 16th Street near today’s Jackson Medical Complex.

When the ‘Soldier Poet’ died on April 17, 1948, he was not only remembered for all that he had accomplished in his life, but also for all those who he inspired. He was considered a trailblazer for other aspiring black attorneys and is remembered fondly as the man who had to overcome a lot of obstacles to pave the way for others in his community to have a chance to realize the American dream.

Resources:

Florida Historical Quarterly: “Florida and the Black Migration”, Jerrell H. Shofner, 1978

Caplin News: “Richard E.S. Toomey set the path for Miami Lawyers, Part 4”

The Colored American: “Lieut. Toomey Reads”, April 26, 1902.

The Colored American: “In Honor of Lieut Toomey – Admirers of His Verses Gather at the Second Baptist Church. A Literary and Musical Feast”, March 21, 1903.

Miami Herald: “Colored Board of Trade Wants Good Paving”, August 27, 1915.

Miami Daily Metropolis: “Temperance Meeting in Colored Section”, September 10, 1917.

Miami Daily Metropolis: “Taxing District to Build School in Colored Town”, December , 1917.

Miami Daily Metropolis: “State Officials and Negroes Meet in a Conference”, May 9, 1919.

Miami Herald: “Negro Uplift Association Gives Reason for Unrest”, June 2, 1919.

Miami Daily Metropolis: “Governor Promises to Guard Negro Interests”, June 11, 1919.

Miami Herald: “Issues A Call for State Convention”, March21, 1920.

Miami Daily News: “R.E. Toomey, 87 Dies; Attorney and Soldier”, April 19, 1948.