Petit Douy in Brickell

The history of the mysterious French chateau along Brickell Avenue and SE Fifteenth Road in Miami, Florida. This building was historically designated on May 31, 1983.

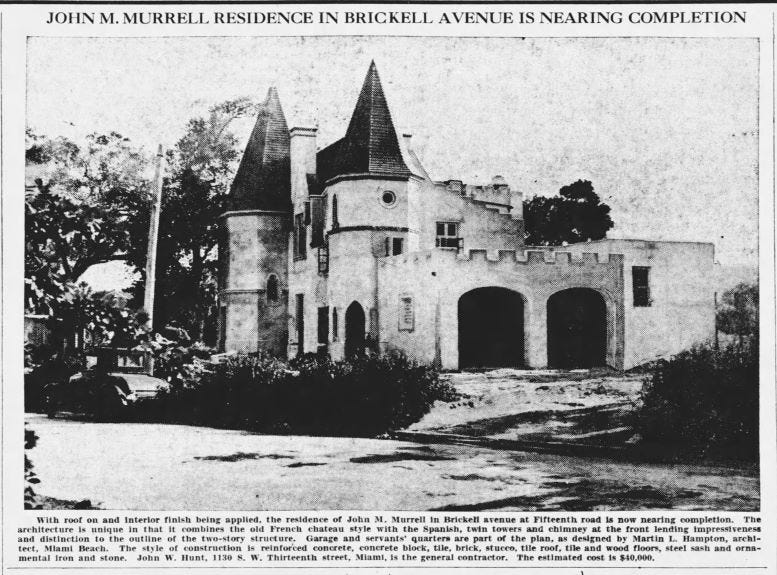

At what was once the southern edge of the city of Miami, at the corner of Fifteenth Road and Brickell Avenue, stands a unique French chateau on an oolitic limestone ridge that is one of the highest points in Miami’s southside neighborhood. The residence captured the impetuous and artistic creativity of the couple who built it. The structure is more than a grandiose architectural marvel, it was home to the Murrell family for more than fifty years.

While the house they built in 1931 provides modern day Miami residents an artifact from the days of Brickell Avenue’s gold coast era, the couple who built it left a legacy of charity and a fighting spirit for the causes they deemed important. The building is more than a reminder of Brickell’s past and will soon be brimming with life once again when it opens as Chateau Miami, the newest restaurant concept by chef Clay Conley. This is the story of Petit Douy.

John Murrell Moves to Miami in 1920

After getting married to Harriet Clark, daughter of Florida Congressman Frank Clark, John Murrell moved to Miami to practice law in 1920. He attended the University of Florida for his undergraduate degree and then earned his law degree from Stetson University in 1919, at which time he passed Florida’s bar exam in preparation for his move to South Florida to begin practicing law.

In July of 1921, John formed a firm with his brother in-law, Frank Clark Junior, called Clark and Murrell, and they opened their office in the Townley Building in downtown Miami. The firm’s client list included the Brickell family and George Merrick. It was Frank Junior who was named co-executor, along with Maude Brickell, for the will of Mary Brickell, after her passing in 1922. However, the dispensation of the estate hit a snag when four of the Brickell siblings contested a provision of the will that bequeathed Alice a cash payment of five thousand dollars that the other siblings were not provided per the terms of Mary’s will. The negotiation between family members reached a stalemate when John Murrell intervened and resolved the dispute with a compromise agreement between the siblings.

While the settlement of Mary Brickell’s will was amicably resolved for the family, it led to the end of the Clark and Murrell law firm only a year after it was formed. John confirmed that differences between the partners over the settlement of the Brickell estate was the reason for dissolution of the practice. This dispute not only ended the partnership but led to a lawsuit over unpaid fees owed to John. The dispute got so contentious that, during one court appearance in July of 1923, Murrell and his brother in-law got into a fist fight in the courtroom.

Despite the quarrel with his brother-in-law, John and Harriet’s marriage proceeded blissfully as they assimilated into Miami’s social scene. They would often host events in their Coral Gables home and were frequent mentions in Miami’s society page. The pair also celebrated the birth of their son, John Murrell Jr., who was born on January 4, 1921. He was the couple’s only child.

The Murrell’s were living a prosperous lifestyle when tragedy struck on June 15, 1930. The family was traveling by automobile in Anderson, South Carolina, when they were hit by a drunk driver. John Sr. suffered a broken pelvis, but his wife, Harriet, was killed on impact. Their son did not suffer any injuries in the accident but was traumatized by the loss of his mother and injuries to his father. John Sr. spent four weeks recovering from his injuries in a South Carolina hospital and once released, was confronted with continuing life without his wife and the mother of his son.

John Meets Ethel (“Sheelah”)

Within a year of Harriet’s untimely death, John met his second wife while she was vacationing in Miami. Ethel Browning, known as Sheelah to her friends, took a cruise from San Francisco to Miami, through the Panama Canal, to explore a different part of the country. While she was enjoying the spoils of South Florida, she met the widower, and the chemistry was instant and undeniable.

Sheelah was the granddaughter of a pioneer family who had a large role in the early history of Laramie, Wyoming. Hailing from the first state to grant women the right to vote, and first to elect a woman governor, Sheelah’s rearing in Wyoming shaped her sensibility when it came to women’s rights. Her grandfather, John Connor, owned an inn called the Connor Hotel which was in downtown Laramie. One of the hotel’s visitors in the early 1900s was Teddy Roosevelt, who was photographed on a horse with four-year-old Sheelah during one of his hunting trips to Wyoming.

When she was ready to experience life outside of Wyoming, Sheelah traveled east to attend school at Chevy Chase in Washington, DC. It was in Washington DC where she was introduced to her roommate’s brother, Ken Browning, who was heir to the Browning rifle fortune. Ken’s father was John Moses Browning who designed the first semi-automatic shotgun that was used extensively during World War I. The Browning Arms Company was founded in Ogden, Utah by John Moses and his brother Matthew in 1878 and is still in business today.

After the two graduated from school, they moved to California and got married in October of 1924. Ken went into the automobile business as a salesman. However, the marriage became turbulent due to Ken’s penchant for drinking. When Sheelah filed for divorce, she declared that her husband became intoxicated so often he was unable to tend to his business as a car salesman. A judge granted her a divorce, something that was rare during the time, in November of 1929 on the grounds of ‘habitual intemperance’ by her husband. Less than two years after the divorce was finalized, Ken was killed when a keg of gun powder exploded in a cabin that he rented during a hunting trip.

After initially meeting in Miami, John and Sheelah spent a lot of time together. It had been a whirlwind romance when the couple decided to get married in a civil ceremony at her mother’s residence in Beverly Hills, California. Shortly after the first ceremony, the couple renewed their vows at the Church of Monserrate in Havana, Cuba on June 7, 1931. Having exchanged vows for the second time, the Murrells were ready to begin their life together in Miami. Prior to constructing their honeymoon home, the couple moved into the Granada Apartments in downtown Miami.

Petit Douy Built in 1931

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.