Realty Board Building in Downtown Miami

The Realty Board building in downtown Miami was the largest realty board structure in the nation when it opened on March 29, 1926. This is the history of the edifice.

By 1924, Miami’s downtown skyline was developing rapidly along the Biscayne Boulevard corridor, and within the Central Business District centered around Flagler Street. Many of these skyscrapers of the day would be characterized as mid-rise commercial, residential or hotel buildings today. One of the mid-rise buildings that loomed large outside of the aforementioned districts was the Realty Board Building which opened in the spring of 1926.

Given the expectation of endless growth in the real estate sector during the 1920s, Miami’s Realty Board saw a rapid increase in their membership during this time and felt optimistic about the future. The leadership of the Realty Board leveraged that optimism to pursue a permanent home as grand as their vision of Miami’s future. This is the story of the building envisioned by the Realty Board and its 44-year history at 329 NE First Avenue.

Building Announced in 1924

On June 25, 1924, the president of the Miami Realty Board, Lon Worth Crow, appointed members to a building committee to envision and facilitate the construction of the finest realty board edifice in the nation. The members of that committee were Frank J Pepper, chairman, and B.B. Tatum, E.M. Lee, D.E. Wilson, L.B. Manley, R.A. Morrison, and George S. Spencer.

It only took the committee 60 days to recommend a location, an architectural firm, a building design concept, and a general contractor to construct the building. On Wednesday, September 3, at the weekly Realty Board luncheon, which was held at the Rendezvous Tea Room in the Brickell neighborhood, Crow announced that the committee had made their recommendations, and each was accepted by board members of the organization. The Rendezvous Tea Room was once the residence of Miami Beach co-founder Carl Fisher.

The architect selected was Martin L Hampton, with E.A. Ehmann as associate architect. The general contractor job was awarded to the Fred T. Ley Company, which had also been the general contractor for the James Deering Estate (Vizcaya), and was working on the Cortez Hotel, Vale Arcade, and several other buildings in Miami when they were awarded the contract. The estimated cost of the project was projected to be $650,000 at the onset of the project.

The location selected for the building was several blocks north of Flagler Street at the 300 block of NE First Avenue. Once completed, the 15-story building would stand out among the other structures in this quarter as one of the tallest buildings outside of the central business district and the Biscayne Boulevard corridor.

At the June 25th luncheon, L.W. Crow also announced that the project would begin on October 1st, and would be completed by July of 1925. Given the volume of buildings being constructed at the time, these estimates would prove to be overly optimistic.

Design and Features of the Building

The building design, Florentine Gothic, was chosen to ensure that the edifice would be distinct and rank among the finest Realty Board buildings in the country. Based on the description of materials used and the track record of the architect, the composition and appearance of the structure would include neo-classical features of the Italian Renaissance era including the two-story pointed archway entrance and the decorative observation tower at the top of the building.

The composition of the structure was described in the Miami News as follows:

“The piers of the cloister will be limestone to the second floor and polychromed terra cotta to the fifteenth, where they merge into the intricate detail of the highly decorated top floor. The floors throughout the entire building will be of terrazzo marble and the corridors will be lined with Faience tile to the full height of the transform line. The interior trim will be a high grade of selected red gum.”

The building included two high-speed elevators, one which made stops at all levels and the other dedicated to the top floor. The ground floor included a store and a 24 by 32-foot entrance with a dining room located at the rear of the lobby. In total, there were 182 offices between the second and 14th floors while the top floor was occupied entirely by the sponsor of the building.

The 15th floor was designed and used exclusively for the Miami Realty Board. The west end of the floor was an auditorium that spanned the entire breadth of the building. The dedicated elevator was located next to the auditorium and opened to a 16 by 19-foot foyer where a receptionist desk and switchboard were located. On the north side of the floor was a committee room and a library, and on the south side was the office of the executive secretary and a map room, which included equipment to handle the over 2,000 maps in the possession of the Realty Board.

Across the entire breadth of the east end of the building was a fully furnished club room for use by the Realty Board members and their associates. This space was described by the Miami News writer as follows:

“The club room will have a 15-foot beamed ceiling, and will be paneled in highly grained red gum. At the south end of the club room there will be a large open fire place, built of structural stone. Every feature of the club room has been designed for utmost comfort, and is expected to be the finest appointed club in the South.”

The building also included an observation tower on the roof of the structure providing a birds-eye panoramic view of the entire city. The tower provided a distinctive feature at the top of the structure to ensure that the Miami Realty Board building loomed large in Miami’s emerging skyline.

Behind Schedule in 1925

While the hope was that the project would start in October of 1924, the official groundbreaking did not occur until March 15, 1925. The general contractor was granted their building permit nearly a month later, on April 9th, which put the undertaking behind schedule from the onset.

By October of 1924, a Miami Herald article wrote that the Miami Realty Board project was well behind schedule and needed to accelerate the development pace. The entire city was experiencing a shortage of cement, lumber, and other supplies which put a strain on the progress of the double and triple-shifts that were rushing to complete projects on time.

It may have been this frantic pace of construction that led to the perception, more than four decades later, that the Miami Realty Building was poorly constructed. Whether it was short cuts taken to compensate for lack of critical materials, or a construction crew that was rushed and worked around the clock, it didn’t take long before there were complaints about the quality of craftmanship of this building.

A little more than a decade after the opening of the building, on July 15, 1938, one of the elevators unexpectedly dropped four stories with seven passengers on it. No one was seriously hurt, but the event led many to believe that this was a sign of problems to come with the construction and maintenance of the building. A few decades later, as the building was prepared for demolition, Miami Herald writer Nixon Smiley wrote: “the faults of the Realty Board Building were covered by plaster and paint.” While it was lauded as a beautiful work of architecture in 1926, the façade hid a lot of problems with the craftmanship.

Dedication in 1926

The edifice was formally dedicated when a crowd of 3,000 people joined the Miami Realty Board members for a tour of the building in an open-house format from 10:00am – 5:00pm on Monday, March 29, 1926. Dedications of this type attracted a lot of onlookers as a form of entertainment for South Floridians. Given the number of building dedications in the city during the mid-1920s, residents kept quite busy exploring the city’s ever evolving skyline.

The building, which sat due east of the Grammar School building, was decorated with floral arrangements throughout the common areas and the top floor. The Grammar School was Miami’s first school house, and the land it sat became the location of the Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office in 1933. The Realty Board Building occupied part of a city block that included a variety of old apartment buildings and hotels that had been part of the Miami streetscape for more than a decade before the Realty Board’s tower was completed in 1926. The Dean Apartments, directly south of the Realty Board structure, had been open since 1912, and the Rutherford Hotel, south of the Dean Apartments, opened in 1906.

The board members provided a tour of the fifteenth floor for all interested parties. They provided a glimpse of the intricacies of the map room, and the extravagance of the club room. The building was well received, and newspaper writers declared it one of the finest structures in the south. Newspaper correspondents shared a very different opinion several decades later. The commercial tower was nearly fully occupied when it opened and included the office of architect E.H. Ehmann and real estate institutions such as the Greater Miami Apartment House Association.

WQAM Tenant in 1930

By the end of 1926, a massive hurricane had devastated downtown Miami and surrounding areas, the building boom had ended, and the region had entered into an economic depression three years earlier than the rest of the country. These factors contributed to financially difficult times for the Miami Realty Board which forced them into making some tough decisions. In 1930, management decided to vacate the 15th floor and consolidate into one of the lower floors. This left the luxurious penthouse office available for a new tenant.

It was the Miami Broadcasting Company, parent of the WQAM radio station, that made the bold decision to lease and retrofit the former offices of the Realty Board into their corporate offices and broadcast studio. On Saturday, November 29, 1930, WQAM conducted their first live broadcast, beginning at 8am, from the top floor of the Miami Realty Building to thousands of listeners. The equipment and furnishings in the new location cost the company $60,000, which was just part of the overall investment to renovate and move into the top floor of the 15-story tower.

Just prior to relocating to their new home on NE First Avenue, WQAM had split time between the Miami Daily News Tower, broadcasting from March until September of 1929, and the McAllister Hotel, where they broadcasted from September of 1929 until their move into the Realty Board Building in November of 1930. The station remained in the tower at 329 NE First Avenue for 18 years until they moved into the Dupont Building on November 22, 1948.

Postal Building in 1933

The financial downturn for the Miami Realty Board led to more than just downsizing their office space. The economic malaise of the time resulted in a high vacancy rate in the building which compelled the debtholders to force the property into receivership. At the onset of the Great Depression, the building was heavily leveraged and the investors, who held more than $300,000 of outstanding debt, felt it was time to restructure their investment.

By 1933, a group of notable bondholders headed by John W. Bullock, president of the Hart Drug Company from St. Louis, Missouri, formed a corporate entity named the Postal Holding Company, and purchased the building out of bankruptcy for $50,000 cash, and an additional $20,000 to the city to pay back taxes. The building was worth $700,000 when it opened in 1926, which means it was acquired for 10% of its original value in bankruptcy. The Miami Realty Board building was not the only property that Bullock purchased out of receivership in Miami during the 1930s. He also acquired the Fairfax Hotel and Paramount Theater, both located on Flagler Street near NE Third Avenue, out of bankruptcy in August of 1935 for $375,000.

By the summer of 1933, the new ownership group renamed the building the Postal Building. It was also in 1933 when the new Federal Courthouse and U.S. Post Office building opened to the west of the newly named Postal Building. The occupants of the former federal building, which was located on NE First Avenue and NE First Street, outgrew the facility by the early 1930s which prompted the need to build a new and larger building at 300 NE First Avenue. The name of the holding company, and subsequent rename of the office tower to the ‘Postal Building’, may have been influenced by the opening of the new courthouse and post office structure directly across the street.

With a change of name also came a change in composition of the tenants who occupied the building. The Postal Building made the front page of the Miami Tribune when the Miami vice squad conducted a raid on the eleventh floor of the building and busted an illegal horse betting operation on December 30, 1936. Illegal gambling became so prevalent during the 1930s that local and national newspapers routinely reported on arrests of bookmaking operations throughout South Florida. A year after the December 1936 bust, the Postal Holding Company sold the building to Maurice Baskin, the president of the Universal Equipment Company, for $150,000 in October of 1937.

Pacific Building in 1945

By the late 1930s, the building was gaining some notable tenants including the Venezuelan Consulate, and the Columbia Tech Institute, which opened a satellite art and drafting school in Miami. During World War II, the Postal Building became the home to the recruiting and training offices for several branches of the armed forces. The Navy occupied an entire floor to become Miami’s official naval recruiting office, and the Women Accepted for Volunteer Services, or WAVES, opened a training center in the building. WAVES was a division of the U.S. Navy which was organized during World War II to leverage the talents of women for projects related to the war effort. In addition, the recruitment and manning office for the War Shipping Administration established offices in the Postal Building to attract candidates for the Merchant Marines.

War time in Miami provided a lift in business for the owners of the Postal Building. As World War II neared its end, Baskin profited by more than $100,000 when he sold the building for $260,000 to the Pacific Management Group in June of 1945. In just under eight years of ownership, Baskin grew the value of the property to what would become its highest level since the crash of the real estate boom shortly after the building opened in 1926. However, the construction cost of the building in the mid-1920s still exceeded the value of the building nearly 20 years after its opening.

Phil Warner, president of Pacific Management Group, purchased the building and slowly began the renaming process. Within a year of the sale, the building began being referred to as the Postal Pacific Building, and by 1954, it was officially renamed to the Pacific Building, dropping the ‘postal’ out of its moniker. While the prior two ownership groups were able to make money on their investment in the property, Warner was not so lucky. It was during his proprietorship that the building began a downward spiral and ultimately was condemned by the city in the mid-1960s.

Beginning of the End

During the late 1950s, the Pacific Building began to experience high vacancy rates as demand for downtown office space declined. In 1960, as a response to the diminished demand for workplace rental, Warner converted the top 9 floors of the building to a hotel which he branded as the Pacific House Hotel. The bottom six floors remained office rentals, but an appetite for a work environment that shared elevators with hotel guests made the building even less attractive to prospective legitimate businesses. As a result, the Pacific Management Company became less selective when it came to the clientele to whom they leased office space.

In February of 1962, the building was once again the scene of a vice raid on an illegal gambling operation in an office on the fourth floor. A year later, in March of 1963, the building was in the news again when they leased an office on the fifth floor to three members of the American Nazi Party (ANP). On March 4th, Miami City Attorney, Robert D. Zahner, authorized a surprise raid of the office in order to shut it down. Although Zahner threatened to find any technicality to chase the Nazis from the building, and ultimately out of the city, the occupants of the office maintained that they had no intention of being forced out of Miami. Within a year, the office was vacant the three men did leave town. One of the defiant ANP members who was present during the raid, John McClure, was later convicted of murder for shooting a Georgetown student in Washington, DC, in June of 1968.

Condemnation of Pacific Building

Throughout the decade of the 1960s, the Pacific Building fell into a deeper state of disrepair. Vacancy rates for both the office space and hotel rooms did not provide Warner with enough revenue to properly maintain the building. By the mid-1960s, cement spalling led to chunks of concrete falling off the building and onto the adjacent sidewalk creating a safety hazard for pedestrians passing by the building. The headline in the May 4, 1965, edition of the Miami Herald read: “Office Building Faces Shuttering Over Safety.” This was the beginning of a long debate about what to do about the derelict structure in what a journalist for the Miami News referred to as the city’s “edifice complex.”

The Pacific Building had gone from a striking architectural gem to an eye-sore and safety hazard. Once the building was shuttered by the city in 1965, Phil Warner quit paying property taxes on the building and absolved himself of any responsibility for the structure. This left the city and county to account for how to get rid of the abandoned edifice before someone got hurt or was killed.

The structure was boarded up, but not impenetrable for vagrants. From 1965 until it was razed in 1970, the fire department was called to the building on numerous occasions to put out fires. Given that a lot of the fires were started on the highest floors, it had become a safety hazard even for the firefighters. The fire chief pleaded with the politicians to do something about the city’s eyesore as soon as possible.

Given that the block had been targeted for urban renewal, the city expected the county to seek federal money for all or part of the demolition. Both municipalities treated the building as a hot potato, and each argued that they did not have the more than $100,000 needed to demolish the 15-story building. The county applied for federal funding to help pay for the demolition cost, but the application was denied.

The back and forth between the city and county over which entity should take responsibility for the cost of the demolition played out in the local newspapers for the better part of four years (1966 – 1969). It was the plan to build a downtown campus for Dade Junior College that provided the municipalities with hope to cobble together funds to pay for the demolition. This provided a different avenue to request federal and state funds as part of a larger project.

Demolition in 1970

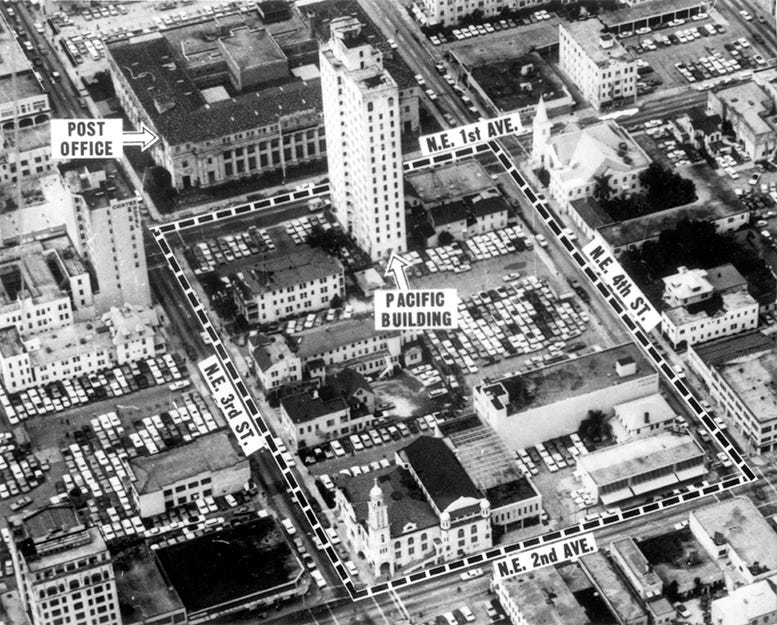

Once a decision was officially made to demolish the Pacific Building by Metro Dade on February 8, 1968, the waiting game began. The county needed to wait on the federal government to appraise the buildings on the 300-block of NE First Avenue, which extended east to NE Second Avenue, and south to north from NE Third to NE Fourth Streets. Once this process was completed, the funds were made available to the county to assist with demolition of the 15-story building.

However, after Big Chief Wreckers was awarded the contract to demolish the entire block, including the Pacific Building, there was a disagreement and another delay. The demolition company expected to be able to use “controlled explosives” to implode the building, but the county required that the 15-story edifice be razed without the use of dynamite. The principals of Big Chief sued the county, but ultimately were required to follow the terms of the contract and to raze the building without the use of explosives, using a crane and bulldozers to slowly bring down the building one floor at a time.

Demolition of the Pacific Building began in May of 1970, and after a delay to resolve the court battle, was completed on September 30, 1970. Although the structure was not that old, only standing 44-years at the time of demolition, it was a victim of poor workmanship, lack of maintenance, and progress. While most of the buildings that were removed from the 300-block of NE First Avenue were also relics of the 1920s building boom and earlier, it was the Miami Realty Board Building that opened with so much pomp and circumstance. It stood as an imposing tower on an island of low-rise buildings in its quarter of downtown Miami in five different decades.

After the block was cleared, it was ready for redevelopment into a downtown campus for Miami-Dade Junior College. Building One, which opened a few years after the demolition of the Pacific Building, now occupies the block where the 15-story tower once stood.

Resources:

Miami News: ‘Realty Board Lets Contract for New Home’, September 9, 1924.

Miami Tribune: ‘Work Will Start on Home of Miami Realtors on October 1; 15 Stories; To Cost $650,000’, September 10, 1924.

Miami Herald: ‘Reservations Made in Realty Building’, September 11, 1924.

Miami Herald: ‘Break Ground Today for Realtors Home’, March 11, 1925.

Miami News: ‘Permit Issued’, April 9, 1925.

Miami News: ‘Realtors Open New Structure with Reception’, March 30, 1926.

Miami News: ‘WQAM Opens New Studios in Realty Building’, November 29, 1930.

Miami Herald: ‘Miami Realty Board Building Purchased’, January 3, 1933.

Miami Herald: ‘Purchase Arranged for Postal Building’, July 31, 1935.

Miami News: ‘$150,000 Paid for Downtown Building Here’, October 19, 1937.

Miami News: ‘Miami Elevator Falls 4 Storis’, July 15, 1938.

Miami News: 'Postal Building Nets $260,000’, June 20, 1945.

Miami News: ‘Raid Starts Drive to Oust Nazis’, March 4, 1963.

Miami Herald: ‘Office Building Faces Shuttering Over Safety’, May 4, 1965.

Miami Herald: ‘Relic of Boom Days Crumbling?’, September 29, 1967.

Miami News: ‘Enough to Give Us An Edifice Complex’, January 10, 1968.

Miami News: ‘Metro Finally Orders Pacific Building Razed’, February 8, 1968.

Miami Herald: ‘Fireman are in a Huff’, February 20, 1969.

Miami News: ‘New Campus Step Closer to Construction’, January 24, 1970.

Miami Herald: ‘Once-Proudest Tower Gives Way to M-DJC’, May 7, 1970.

Miami Herald: ‘Wreckers to Switch Tools to Raze Pacific Building’, August 13, 1970.

Images:

Cover: Aerial of NE Third Street in 1969. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.

Figure 1: Rendezvous Tea Room in 1924. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.

Figure 2: Miami Realty Board building on February 15, 1926. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.

Figure 3: WQAM announces move to the Miami Realty Board Building. Courtesy of Miami News.

Figure 4: Article in the Miami Tribune published on July 31, 1935. Courtesy of Miami Tribune.

Figure 5: Pacific Building prior to demolition in 1970. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.

Figure 6: Future footprint of Miami-Dade Junior College building one in downtown Miami. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.

Figure 7: Article in Miami Herald on February 20, 1969. Courtesy of Miami Herald.

Figure 8: Pacific Building during demolition in 1970. Courtesy of Florida State Archives.