Spanish Missions on Miami River – Part 2 of 2

Part two of a two-part series on the Spanish Mission periods along the Miami River.

Early in 1567, Father Juan Rogel, S.J., and Brother Francisco Villareal, S.J., returned to La Florida, the former moving to a military outpost near Charlotte Harbor in Calusa Indian country, while the latter settled among the Tequesta Indians near the confluence of the Miami River and Biscayne Bay in southeast Florida. Menendez officially inaugurated the mission at Tequesta, remaining there for several days.

According to one account, the Spanish leader was “very well received” by the natives, who “took him for their elder brother.” Menendez left behind thirty soldiers and an undetermined number of carpenters to build a blockhouse at Tequesta. After initial success, the Jesuit mission was plagued with problems. Yet progress was evident when Menendez returned to Tequesta and noted that the natives took part in devotions twice daily “in front of a large cross.”

When the Spanish admiral left Tequesta after this visit, he took three important members of the group, including Chief Chequesta, with him to the court in Seville, Spain, where they received a “tumultuous reception.” Later, in the great cathedral in Seville, Menendez witnessed the baptism of five Florida Indians, three of whom were denizens of the mission at Tequesta.

Another aspect of Brother Villarreal’s spiritual work was revealed in a letter written by him to Father Juan Rogel, his southwest Florida counterpart, on January 29, 1568. This missive is considered the first letter penned in Miami. In it, the Jesuit missionary described his work and the challenges facing his ministry at Tequesta. "I have been teaching doctrine to the Indians up to fifteen years of age,” he wrote. “Those who attend, most of them, know the four prayers and nearly all the commandments.” Villareal also taught “doctrine in the house of the chief where many adults are present, and I believe they learn it too although they do not recite like the children. I think the chief is learning too. I teach them the prayers and commandments and afterward the credo.”

Brother Villareal continued his efforts to convert the Tequestas to Christianity. To bring large numbers of Indians to services, he informed Father Rogel: “We hold fiestas with litanies to the cross. We have put on two comedies (comedias), one on the day of St. John when we were expecting the governor (a reference to Pedro Menendez). This play had to do with the war between men and the world, the flesh and the devil.” Sometimes he conducted “miracle plays,” which were dramatic presentations based on Biblical accounts of the struggle between good and evil, God and Satan. One Jesuit priest suggested that this approach meant that Brother Villareal had “introduced European theater to the new world.”

Brother Villareal’s letter also expressed his frustration over the difficulties of converting the native population to Christianity. “Even though I do not think that there is anyone who says he does not wish to become a Christian,” he wrote, “they have great difficulty in learning the doctrine, and accordingly, they do not come to it.” Brother Villareal added: “I have tried to make the Indians like me as your reverence commanded and brought a little corn for this purpose…(but) up to now I have nothing to give them and when there is nothing to give them, I believe there is little friendship.”

The Jesuit brother observed that while the natives “now have food from the whales they kill and from fish…they suffered from hunger for two or three months so that they failed to attend (spiritual gatherings) because they all said they were hungry and begged that little which I had to give them.” Brother Villareal also noted, happily, how several sick children “have become well, as they put it, after I have spoken the gospels.” Finally, the Jesuit complained of “some of the burdens of the land…I am referring to the three or more months of mosquitoes we have endured, in which I passed some nights and days without being able to sleep for an hour.” What sleep there was resulted from the brother lying close to “the fire and immersed in clouds of smoke, as one could not survive in any other way.” Villareal ended his missive on an upbeat note, however, hoping that “some (of the Tequestas) will be great Christians.”

Two months after Brother Villareal’s letter, the Spanish abandoned the mission at Tequesta. Conflicting reasons are offered for its closing. Historian Arva Moore Parks believes that “the evidence seems to indicate that Spanish soldiers incited the Tequesta Indians, forcing them to retaliate.” In this venue of increasing animosity and hostility between two widely variant cultures, the Jesuits left. Brother Villareal and Father Rogel were recalled to Havana where the Society of Jesus was preparing to establish a college.

Although the Society would ultimately give up Florida for more fertile missionary fields elsewhere in the southern tier of North America, they were not quite finished. In December 1568, a second mission opened at Tequesta under the direction of Father Antonio Sedeno, S.J. The apparent reason for this development was the religious fervor of Don Diego, the Christianized name of the brother of Chief Tequesta. After his baptism in Seville, Don Diego described for his brother this inspirational experience. Chief Tequesta, himself, grew eager for the return of the missionaries even ordering his people to build a house for the religious and sending someone out daily to look for their ship. The Spanish had also decided to return to Tequesta and reopen the mission, which they did in December 1568 under the direction of Father Antonio Sedeno, S.J.

Father Sedeno reached Tequesta on December 7, and described the colorful events surrounding the arrival of his ship. The “Indians came on board, and with them the chief and Don Diego and we arranged the peace, and he, through a writ of the notary, gave obedience to King Phillip II (of Spain), promising to become a Christian with all his people, and as a pledge of this they brought two beautiful pins for a cross, which was made and planted where the first one had been, while singing litanies with great devotion. And all went to adore it with great reverence and showing great joy.” Sedeno also reported that the Indians “have submitted to His Majesty, and the chief told me that he and all his vassals wished to become Christians. For that purpose, I have left a priest here with some young men; and so that he may enjoy more security, I am going to San Augustin so that some soldiers may come.”

Despite its auspicious beginnings, the second mission, of which there is little known, was abandoned in 1570. Documents written a few years after its closing point to a general deterioration in the relationship between the Spaniards and the Tequestas. Soon after, the Jesuits abandoned Florida as a missionary field. In their place came the Franciscan friars, who were much more effective in converting the native populations to Roman Catholicism. Their success heralded the “Golden Age” of the Florida missions, which lasted till the beginning of the 1700s.

The Jesuits returned to Florida as missionaries nearly 200 years after they had closed the second mission at Tequesta. This move was prompted by a petition issued in 1743 by Indians in the Florida Keys requesting the governor of Cuba to send missionaries. On June 24, 1743, the governor complied by dispatching Fathers Joseph Maria Monaco, S.J., and Joseph Xavier Alana, S.J., to build another mission in southeast Florida. Three weeks later, the two Jesuits anchored near the mouth of the Miami River.

Archaeological evidence points to the location of that mission near today’s Wachovia Financial Center in the southeastern sector of downtown Miami. The missionaries built a stockade near the mouth of the Miami River with help from men from the garrison. By then, there were just 180 Indians living in Tequesta, one-half of whom were children. From the beginning of this brief mission, the Jesuits faced hostility from the adults of the community who had heard of earlier problems with Europeans.

After Father Alana filed a report to Juan Francisco Guemesy Horcasitas, the governor of Cuba, recounting his problems at the mission, the latter requested permission of the King to close the mission believing that “the whole effort was fruitless and a waste of money because of the Indians’ rootlessness and unadulterated fickleness.” This decision marked the end of the Spanish Jesuit mission system in Florida.

Catholicism would not return to the Miami area till the late 19th century following an appeal by William Wagner, a homesteader, for a priest to periodically administer the sacraments in a desolate community then called Fort Dallas or Miami. However, the Jesuit missions should not be looked upon as a failure for they planted, albeit temporarily, elements of Spanish culture and religion in a native culture that was many years away from that of the European missionaries and their Spanish champions. In addition, it has provided modern-day contemporaries wonderful insights into this oft-overlooked period of Miami’s history.

Images:

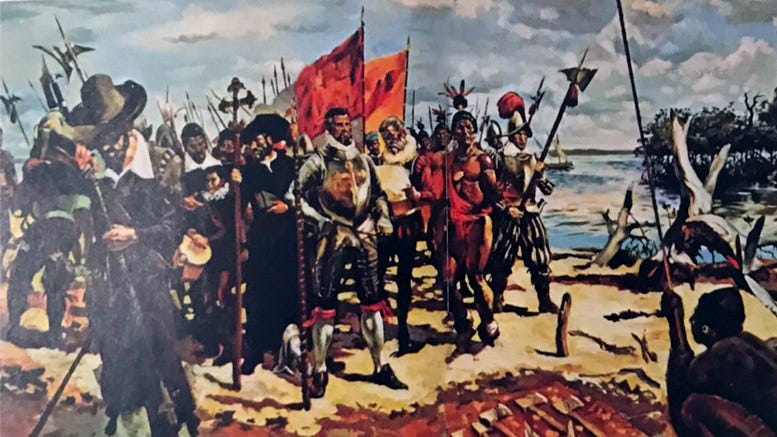

Cover: Chief Tequesta welcomed Pedro Menendez de Aviles in 1568. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

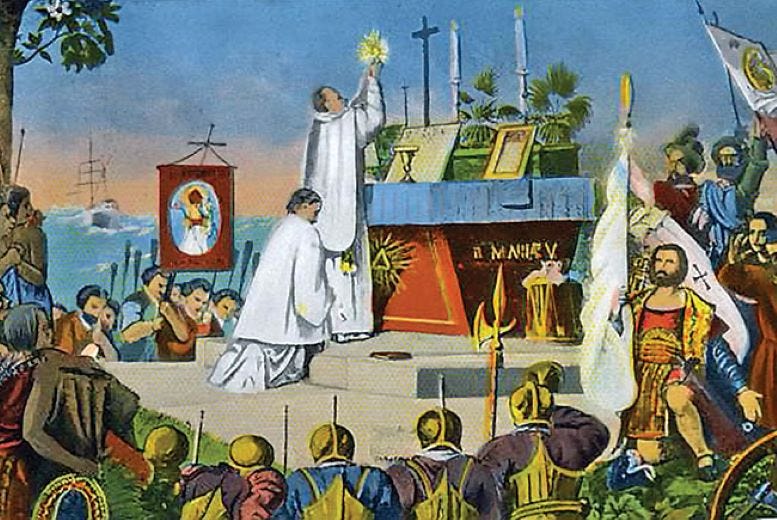

Figure 1: Spanish Mission in 1568. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 2: Giralda Tower in Seville, Spain.

Figure 3: Chief Tequesta mural at Saint Patricks Church on Miami Beach. Courtesy of St. Patrick Church.