Tobacco Road Bar History - From Bakery, Speakeasy to Miami City Landmark

The history of Miami's Tobacco Road Bar which was formerly located at 626 South Miami Avenue in the heart of the Brickell neighborhood.

On November 17, 2012, the Tobacco Road bar in Miami celebrated what was widely believed to be its one-hundred-year anniversary in business. The bar proudly touted that their liquor license dated to 1912 which made it South Florida’s oldest drinking establishment.

When the liquor license was allegedly issued, Miami was a little more than sixteen years of age. The city was founded in 1896. Given the claim, Miami would have been entering adolescence when its first liquor license was issued. By today’s legal drinking age, the city would have been too young to enjoy what the license provided.

While the tale of Tobacco Road’s liquor license may be urban legend, the establishment had a fascinating story. During its last years in business, locals referred to the place as “The Road”. This road provided plenty of wild turns throughout its history. The place continually reinvented itself as Miami evolved through the years. This is the story of Miami’s oldest saloon.

Prohibition Started Early in Dade County

Prior to there even being a building at the future home of Tobacco Road, Dade County voted itself dry. On a rainy night in October of 1913, the rural northern section of Dade County tipped the scales to ensure the sale and consumption of alcohol was outlawed. The county was officially dry in January of 1914. Prohibition in Dade County began six years sooner than it did for the rest of the country.

The law change in Dade County further complicates the tracking of the liquor license allegedly issued in 1912. Regardless of who had possession of the license, it became invalid as of January 1914, and would have required reissuance after the vote to repeal the Eighteenth Amendment. The ratification of the Twenty First Amendment ended prohibition in 1933.

Although Dade County was under the restrictions of prohibition in 1914, laws against selling and consuming alcohol did not stop store owners from covertly serving booze in the confines of their legitimate business. The term for this type establishment was called a speakeasy. It was applied to places you would speak of carefully in public to avoid alerting law enforcement that alcohol was served at the location.

It was a Bakery for Years

According to the Miami-Dade County property appraiser, there wasn’t a building at what would become the Tobacco Road bar location until 1916. The original address was 1812 Avenue D. However, when the Chaille plan was implemented in 1920, the address changed to 626 South Miami Avenue.

J.A. Hall, H.E. Pattern and Warren Williams were the first to be listed at the address in 1917. The three men were listed for only one year. It is likely the trio were responsible for constructing the original building at the location.

The Miami city directory listed a baker living at the address in 1918. The building was both a residential-style bakery and the primary residence of the proprietors. The official name of the business was Rosenquist Home Bakery and it was not listed until the 1919 directory was published.

The bakery was run by Karl Gunnar Rosenquist and his wife until 1925. The Rosenquists were from Chicago and relocated to Miami in 1913. Gunnar had been a baker in Chicago prior to the couple’s move to South Florida.

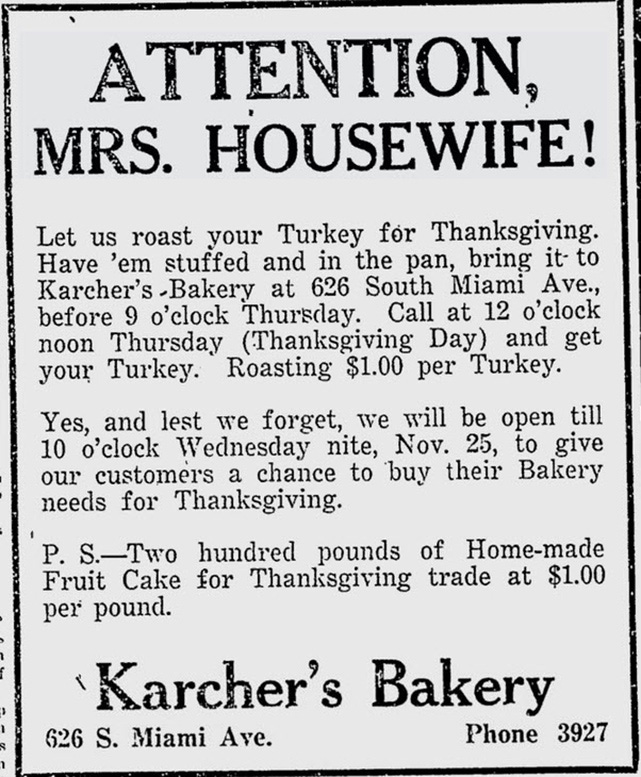

The next business to operate at 626 South Miami Avenue was Karcher’s Bakery. In an advertisement in the Miami News in 1925, Karchers offered housewives the opportunity to bring their turkey to the bakery to be cooked for pickup by noon on Thanksgiving Day. The service was advertised to cost only $1.00. The promotion was intended to make it convenient for customers to buy all of their Thanksgiving dinner baked goods at Karchers as well. The ad also stressed that all bakery goods can be conveniently purchased at the same location.

In addition to running the Bakery, Julius Karcher Jr. ran a real estate office from the same location. During the mid-1920s, Miami was experiencing a big real estate boom. Many business owners were dabbling in real estate while also running their primary business.

Karcher Bakery had a relatively short life on South Miami Avenue. The bakery closed its doors in 1927. The location was listed as vacant in the 1928 city directory.

The Great Hurricane of 1926 was the final blow that officially ended the real estate boom of the mid-1920s. Miami spiraled into economic depression three full years ahead of the rest of the nation. It is probable that Karcher’s Bakery went out of business due to the economic conditions in Miami at the time it closed.

The next bakery to open at the location had an even shorter life. Miller Brother’s Bakery was open for business for only one year in 1929.

The following year, a familiar name returned to 626 South Miami Avenue. Gunnar Rosenquist reopened his bakery in 1930. He once again operated his namesake bakery at the location until 1936.

South Side Bakery took over the business from Rosenquist in 1936. South Side was a common name for the Brickell neighborhood in the early to mid-1900s. It only stayed open for one year and closed its doors in 1938. After the closure of South Side Bakery, the next proprietor kept part of the name but changed the type of business operating at this address.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.