United States Hotel in Downtown Miami

The U.S. Hotel building stood at 201 NW First Avenue in downtown Miami for a century during Miami's formative years. This is the history of that building from opening in 1918 until demolition in 2018.

Nearing its hundredth birthday, the U.S. Hotel stood as a lonely reminder of a past that is slowly disappearing in downtown Miami. It opened in November of 1918 and was razed in May of 2018. Its age and lack of height in an era of verticality rendered the old building obsolete.

Its proximity to the train station made it a popular hostelry in the first half of the last century. The train station was demolished in 1963 at a time when downtown residents were fleeing to the suburbs. The U.S. Hotel lived out its next fifty-five years as a non-descript building in a largely abandoned downtown. This is the story of the United States Hotel building formerly located at 201 Northwest First Avenue.

FEC Passenger Depot Moves to Avenue E

Prior to 1912, the area north of Twelfth Street (now Flagler Street), and Avenue E (now NW First Avenue), was primarily commercial. There were blacksmith’s, foundries, lumber supply depots and livery stables throughout the area. The Sheftall and Baxley company, a general blacksmith and horseshoe specialist, was the primary business operating along the east side of Avenue E, between Tenth and Eleventh Streets (now NW Second and NW First Streets), from the late 1890s through the early 1910s.

However, the area changed when the FEC Railway relocated their passenger depot to Avenue E in 1912. The freight depot already was located along Avenue E since the arrival of the first train to Miami, but the passenger depot was positioned on Sixth Street near today’s Biscayne Boulevard. The approximate location of the depot was where Freedom Tower is located today.

Within two years of the FEC passenger depot opening along the west side of Avenue E, Sheftall and Baxley sold the land in which their livery and blacksmith was located. Beginning in 1914, the east side of Avenue E was beginning to transform into locations that catered to passengers arriving at the FEC train depot.

In May of 1914, Dave Afremow purchased land on the southeast corner of Tenth Street and Avenue E (NW Second Street and NW First Avenue), with the intention of building a hotel. However, the construction of what would become the U.S. Hotel was not started until 1918.

In the meantime, there were a total of nine buildings constructed on the property that Afremow purchased while he waited to build his hostelry. These buildings were later joined together to create the foundation of what would become the U.S. Hotel building.

United States Hotel Opened in 1918

Until construction began for the hotel, the foundational buildings hosted several businesses across from the FEC train depot. The Chicago Carpet Works opened in 1916 at 915 Avenue E. The Dade County Employment Agency operated out of 927 Avenue E. Even the Nazarene Church held services in one of the temporary buildings along the east-side of the 900 block of Avenue E (between today’s NW Second and NW Third Street along NW First Avenue).

Even the Jaudon brothers operated their seed wholesale business in the area in the mid-1910s. The brothers were one of several founders of the Chevelier Corporation and Captain J.F. Jaudon was an important figure in the completion of the Tamiami Trail to Miami.

However, that changed when Afremow realized there was a real opportunity in operating an inn when the Grand Hotel opened a block south of his property. The new hotel opened in the Fall of 1916 and it was an immediate success. The proximity to the train depot provided passengers a convenient place for overnight accommodations. Afremow realized that the timing was right to build what he originally intended to build when he brought the property in the 900 block of Avenue E.

In May of 1918, he announced that he would combine the nine buildings on his property and add a second story to the conjoined set of buildings. The first floor provided retail options for the public and the second floor operated as a hotel. Construction was completed in the Fall of 1918 and the hotel officially opened on November 8, 1918. Walter Nichols signed a lease to manage the hotel.

When the operation was announced in May, Afremow said he was going to call it the American Hotel. However, prior to the opening, the name was changed to the United States Hotel. The signage on the building and advertisements for the establishment shortened the name to the “U.S. Hotel”, and the building was primarily referred to by the shortened name from the date it opened as a hotel.

Lundgren’s Restaurant & Expansion Plans

During the first year of operation, a restaurateur from Denmark remodeled one of the storefronts and opened a Danish bakery and delicatessen. Hilmar Lundgren was trained as a baker in Copenhagen and refined his trade at the Cedar Hurst Yacht Club in New York. He and his wife opened Lundgrens Restaurant in September of 1919, at 915 Avenue E (223 NW First Avenue), just in time for the winter season in Miami.

The restaurant became very well known for the Danish pastries and cakes. Although it was primarily a delicatessen, visitors to the U.S. Hotel were delighted by the baked goods they could enjoy just steps away from the front desk of the U.S. Hotel. Of course, Lundgrens was also popular with the arriving visitors to the train depot across the street from the restaurant. Lundren’s Restaurant was in business for five years before it closed its doors in the Fall of 1924.

By October of 1919, it was apparent to Dave Afremow that there was more demand for hotel rooms than he anticipated. At this time, he owned both the U.S. and Grand Hotels. Both were conveniently located across from the train depot and both were consistently sold out. Afremow announced that he was going to add a third floor onto the U.S. Hotel to accommodate growing demand. A third floor would have increased the capacity of the inn from thirty-five to one hundred rooms.

At the same time, Mrs. J. Hirsh Hood took over management of the U.S. Hotel from Walter Nichols. Hood was the operator of the Majestic Hotel prior to assuming the lease. Nichols continued to manage the lease while Mrs. Hood managed the day to day operations of the business.

Despite Afremow’s plans to expand the U.S. Hotel, it never did add the third floor to the building. While there was not an explanation for why the expansion didn’t happen, the building remained a two-story structure until it was razed in May of 2018.

New Ownership of Hotels in 1927

Within a year of Mrs. Hood taking over management of the U.S. Hotel, Nichols sold his lease to William Sayers and his sister, Mary Broida. The pair had managed The Plaza in St. Petersburg, Florida, until they decided to move to Miami for a new challenge. Walter Nichols announced that he was retiring from hotel management to focus on his other business interests.

The siblings owned the lease and managed the business until Gilbert B. Rowell purchased both the U.S. and Grand Hotels in July of 1927. The Rowell’s would go onto own and lived in the U.S. Hotel for the next thirty-eight years. However, during their stewardship, the Rowell’s found themselves constantly engaged in controversy.

Speakeasy at the U.S. Hotel

Although it isn’t documented how long the Rowells were operating a speakeasy out of rooms on the second floor, there luck as a distributor of illegal booze ran out in 1930. In October of that year, Bessie Rowell, Gilbert’s wife, was nearly the victim of a drive-by shooting. The bullets missed Mrs. Rowell but did lodge into the exterior of the U.S. Hotel. After a car chase, L.G. Morton was arrested for the shooting. He apparently was drunk and upset about something. This event occurred while prohibition was still in effect.

In December of 1930, the Miami Herald and News reported that Bessie Rowell and one other gentleman were arrested for distributing booze out of two rooms in the hotel. Thirty sacks of whiskey and seventy-two bottles of beer were seized and carried through the lobby of the hotel while a large crowd gathered to watch the procession. Perhaps Mr. Morton was a disgruntled customer of the speakeasy and informed on the operation after his arrest in October.

In October of 1931, a judge issued a padlock order for the two rooms where liquor was still being sold at the hotel. The same judge also issued the same order for the Grand Hotel, which the Rowells owned as well. Apparently, the Rowells were interested in providing more than just nightly lodging.

In February of 1932, Judge Halsted L. Ritter ordered a permanent padlock for the two rooms at the U.S. Hotel. In May of the same year, Gilbert Rowell was given two six-month sentences, to be served concurrently, in the Dade County Jail for violating the prohibition law. His wife, Bessie, was freed when Judge Ritter dismissed a similar charge against her.

No Pets Allowed

Following the release of Gilbert from Dade County Jail in the Winter of 1932, the Rowells stayed out of the liquor distribution business and managed to stay out of the news until a confrontation with two blind men in February of 1944.

When a seeing-eye dog accompanied two blind men to check into the U.S. Hotel, Bessie Rowell refused to honor their reservation due to the hotel’s policy about pets. Bessie Rowell explained that some of their guests are asthma sufferers and would be adversely affected by the presence of a dog in the building.

A heated confrontation ensued, and the police had to be called to resolve the issue. Mrs. Rowell agreed to honor the men’s reservation for one night but insisted that they had to find other accommodations for subsequent nights. While the confrontation with the two blind men was bad publicity, it didn’t discourage the Rowells from future confrontations.

The Victory Canteen

In May of 1942, several volunteers formed the Miami chapter of the Victory Canteen to provide services and free meals to military men stationed in the city. The group served doughnuts and hot coffee to the men from 9:00am until 10:30pm every day. Stationary, postcards, books, cigarettes, fruit and candy are the types of items that soldiers could get for free from the Canteen.

Originally, the organization was stationed on the corner of SE First Avenue and Second Street, but they moved to the U.S. Hotel building at 219 NW First Avenue in 1944. The organization garnered mostly favorable press and were lauded for the fine service they provided soldiers and their families stationed in Miami during the war years.

However, on May 10, 1944, the Victory Canteen and the Rowells began a very public squabble. It was on that day when Bess Rowell put a lock on the door of the entrance to the Canteen to keep volunteers out of their location and subsequently unable to provide food and services to military personnel.

Apparently, weeks before this incident, the Rowells turned away a serviceman’s wife and her baby when she wanted to use a room to give her baby a bath. After a fair amount of deliberation, Bess Rowell allowed the woman to rent a room for fifty cents so that she could take time to bath her child. This incident infuriated Florence Blakely, the president of the Victory Canteen and wife of a judge, and she subsequently stopped referring service people to the U.S. Hotel for lodging.

While not having any legal standing, the Rowells found out that Blakely was referring patrons to other hotels and they decided to evict the Victory Canteen without proper notice. The Rowell’s attorney claimed that they gave the proprietors of the Victory Canteen twenty days verbal notice.

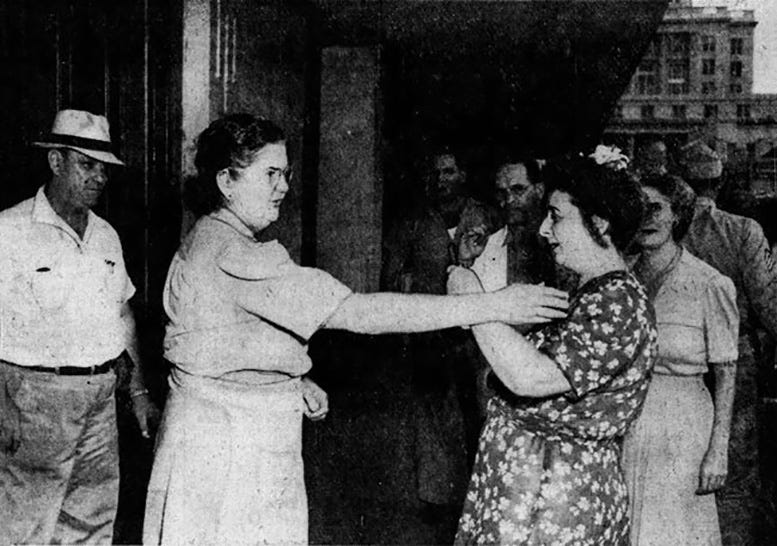

On May 11, tensions escalated, and a confrontation ensued in front of the building at 219 NW First Avenue. Blakely arrived with a hammer and screwdriver and was intent on removing the lock. Bess Rowell stood out front and physically kept Blakely from the front door. In the end, the police were called, and the incident was referred to civil court. Ultimately, the Victory Canteen was able to get access to the building to retrieve their belongings but was forced to move to a new location.

By this time, the Rowells had garnered enough bad press to put any operation out of business. However, they found a way to remain in business until Gilbert Rowell’s death on February 22, 1965. His wife, Bess, died three years earlier, on August 25, 1962.

After Gilbert’s death, the U.S. Hotel closed but the retail establishments remained open for business. The second floor of the building was converted into warehouse and storage. While the retail establishments changed on occasion, the edifice remained a viable commercial building. When a new restaurant opened on the ground floor of 201 NW First Avenue, there was renewed hope for not only the structure but also for the surrounding area in downtown Miami.

Carolina Café

When the Carolina Café opened at 201 NW First Avenue in the Spring of 1993, the Miami Herald headline read “Barbecue, With A Side Order of Urban Renewal”. The restaurant was described as an open-air BBQ joint with southern hospitality. However, what was newsworthy was the amount of investment Anthony Phillips and his partners put into the building.

The owners of the restaurant invested $880,000 to restore the building in preparation for the opening of their restaurant. They stripped the linoleum floors and refurbished the walls. When the original cream-colored floor tiles were unearthed, it brought the new tenants back to 1918 when their location was the lobby of the new U.S. Hotel. Art students from the New World School of the Arts contributed murals that were painted on the refurbished walls.

The opening of the café and the enthusiasm of the new proprietors created a buzz for the old hotel building. The owners of the Café even suggested that they would seek historic designation. Robbie Barrow, the creator of the concept and cook was particularly enthusiastic and optimistic.

In an article in the Miami Herald, dated May 6, 1993, Barrow was quoted saying:

“I had designed this restaurant 15 years ago and never found a place to do it. I saw this building and thought I had died and gone to heaven. I could refurbish this old hotel and put it back like it used to be.”

However, the proprietor’s infectious optimism could not keep the doors open for more than two years. The Carolina Café closed in July of 1995. While the building remained a viable location for boutique retail shops and restaurants, it just plodded along until its current owners decided it was time to evict their tenants and demolish the building to clear the lot for the next big development.

While it took nearly one hundred years for the building to be subject to demolition, it took less than a week to raze the structure. It is likely that the very modest two-story United States Hotel building will eventually be replaced with Miami’s next big residential high rise. In a rapidly changing city skyline, many of Miami's historic building stock can only be memorialized in pictures and remembrances that share their story. At the very least, this article can serve to tell the story of building that fell months short of surviving one hundred years in downtown Miami. If the walls of the old hotel could talk, the stories would be captivating.

Images:

Cover: U.S. Hotel in 1930s. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 1: FEC Depot in downtown Miami in 1940s. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 2: Exterior of U.S. Hotel in 1935. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 3: Ad in Miami Metropolis on November 11, 1919. Courtesy of Miami Metropolis.

Figure 4: Bar at U.S. Hotel in 1935. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 5: Victory Canteen confrontation on May 11, 1944. Courtesy of Miami News.

Figure 6: Demolition in May of 2018. Courtesy of Larry Shane.