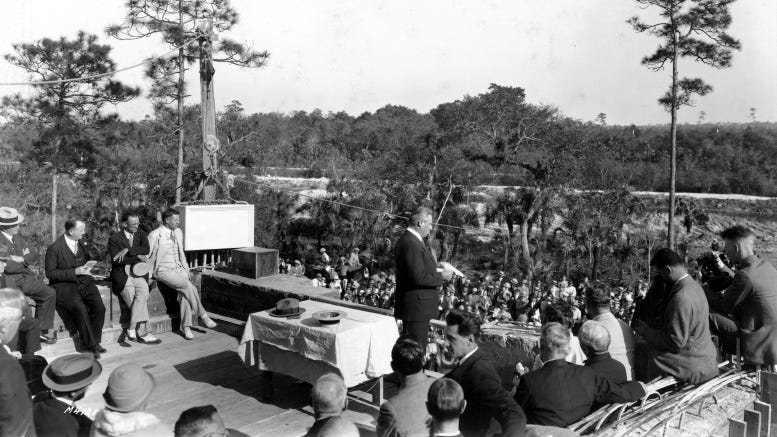

University of Miami Cornerstone Dedication in 1926

On February 4, 1926, George Merrick spoke at the cornerstone laying of the University of Miami. This is the story of the dedication and the beginning of the university in Coral Gables.

More than seven thousand people converged on the site selected for the University of Miami in Coral Gables to witness the cornerstone laying ceremony on Thursday, February 4, 1926. The pomp and circumstance surrounding this event represented a seminal moment in the founding story of this educational institution.

Some of the most influential South Florida residents during the roaring twenties were involved in both the founding of the university and the dedication ceremonies. The school’s most generous benefactor, George Merrick, shared his thoughts on how that day was the proudest moment for him and the biggest day in Coral Gables history. He pledged his support through the donation of land and money in memory of his late father, Reverend Solomon Merrick, who died fifteen years earlier in 1911. In many ways, the cornerstone dedication ceremony was George’s opportunity to memorialize his father.

School Chartered in April of 1925

It was William Jennings Bryan, a three-time presidential candidate and former secretary of state in the Woodrow Wilson administration, who was accredited for spawning the idea for a Pan-American university in South Florida, and given his affiliation with George Merrick, envisioned it would be located in Coral Gables. As the City Beautiful was gaining in popularity, the idea of a school with international appeal was had the support of Merrick, Bryan, and James Deering to name a few of the high-profile dignitaries behind the movement.

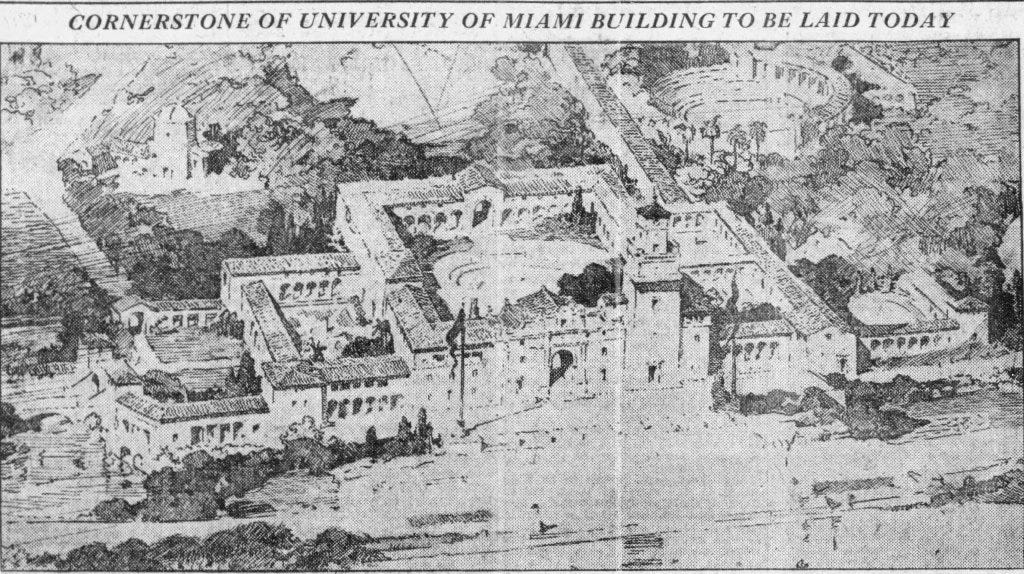

In March of 1925, the concept of an institution of higher education in South Florida had taken root leading to the formation of a board of regents to formalize the pursuit of a university. Judge William E. Walsh, who would become the chairman of the first board of regents, described the idea for an open-air institution of learning which would include outdoor classes being conducted in shell pavilions with a partial roof to maximize light and air flow. Walsh was a recent arrival to Miami Beach when he relocated from Pittsburgh to start his law practice. He went on to become a municipal judge who was a big proponent of higher education. While he wasn’t as focused on the Pan-American concept as Bryan, Deering, and Merrick, he believed the region was ripe for a great outdoor university.

The officers of the first board of regents were Judge Walsh as president, Ruth Bryan Owen, daughter of William Jennings Bryan, as vice president, and Frederic H. Zeigen as secretary and treasurer. Other members of the original board included Judge Mitchel D. Price, author Clayton Sedgwick Cooper, head of the Miami Conservancy for Music Bertha Foster, and impressionist painter Henry Salem Hubbell. The board met for the first time on March 12, 1925, to plan the details of the project and complete the application process.

Frederic Zeigen was made the managing regent for the committee and put in charge of completing the charter application. In the document, he called for the need of at least 160 acres of land for the campus and a budget of up to $15 million. Initially, the proposal called for accommodating up to 5,000 students upon the opening of the university in the Fall of 1926, but the regents felt that the area could accommodate a much larger institution.

The charter was granted by Judge H.F. Atkinson on April 10, 1925. An article in the Miami Daily News described the parameters of the charter as follows:

“The charter provides for the founding in Miami of a university which will have scientific and classical courses, and in addition have a normal school wherein white teachers may be trained. The charter provides that the institution may own up to $10 million of property.”

The provision that spelled out the race of the students who could get an education at the university provided for a policy of racial segregation. This would not change until 1961 when the university trustees voted to end segregation by opening admission to everyone regardless of race, creed, or color.

The article in the Daily News also wrote that “a feature of the institution will be the general establishment of outdoor class rooms.” The next big decision for the board was to select a site on which to build the campus.

Location for Campus Chosen

When the board of regents met for the first time on March 12, Judge Walsh received a wire from Coral Gables founder George Merrick who offered to donate 160 acres of his Coral Gables development to the school, and to make a generous donation to help finance the start of the university. He would ultimately donate $4 million, with part of that earmarked to finance the construction of the administrative building which would be dedicated as the ‘Solomon Greasley Merrick Memorial’ building when it was completed.

However, before the board could decide on accepting Merrick’s offer, they needed to consider the pros and cons of all possible locations. They narrowed their choices down to four possible sites in and around Miami, but ultimately decided to accept Merrick’s offer on May 25, 1925, which provided for 160-acres of land in the Riviera section of Coral Gables.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.