YMCA in Downtown Miami (1918 – 1978)

The history of the first YMCA in downtown Miami which was constructed and operated from Short Street for sixty years. The building was dedicated on May 16, 1918.

Sixty years is a good run for a building in Miami. Many of the city’s early twentieth century structures had a far shorter lifespan. When the YMCA building at 40 NE Third Avenue, aka Short Street, was opened in 1918, it was the culmination of a community-wide effort to construct an institution for the betterment of the city.

By the time it closed and was razed in 1978, sixty years after it opened, it was referred to as the ‘Old Gray Lady’ whose time had passed. John Harold, the Miami Herald staff writer who covered the demolition, summed up the sentiment of the day as “Miami’s old-fashioned downtown ‘Y’ had outlived its usefulness.”

While the YMCA organization still operates in and around the Miami metropolitan area, the loss of the ‘Old Gray Lady’ left Miami’s Short Street missing a symbol of early Miami’s innovative spirit to address problems. What began with an observation by a concerned winter resident led to a city-wide campaign to construct an institution that served the community for six decades.

City Leaders Advocate for Recreation Center

When Paul Keith, operator of the B.F. Keith chain of vaudeville theaters, began to winter in Miami in 1911, he noticed that boys and young men had no place to spend their leisure time except on the streets and in pool halls. In a conversation with pioneer physician, Dr. James Jackson, as well as other city leaders, Keith shared his concerns with the group and offered to put up $5,000 toward constructing a YMCA if the others felt the idea had merit.

Dr. Jackson agreed to lead a committee to solicit the YMCA organization to explore the option of constructing a recreation center in downtown Miami. In September of 1915, the committee met with William S. Frost, a representative of the international committee of the Young Men’s Christian Association (YMCA), who offered to undertake the campaign necessary to raise funds to construct a building that would cost not less than $75,000. Frost would also guide and oversee the construction of the building once the necessary funds were secured. He had extensive experience overseeing the development of YMCA buildings in four other cities prior to the Miami project.

The first fundraising event took place in February of 1916 at which time $103,000 was pledged in a campaign that lasted only one week. Shortly after the fundraiser, the committee purchased two lots for $28,500 on the southwest corner of Avenue A (aka Short Street), and Eleventh Street, today’s NE Third Avenue and NE First Street, for the location of the YMCA building. Once the site was selected, the committee recommended Harold Hastings Mundy to be the architect of the building, who immediately began working with Frost to understand the specifications and standards required by the YMCA organization.

WWI Modifies Plans for the YMCA

As planning for the Y building was in progress, the United States entered World War I. Miami was under consideration by the navy as a training location and the Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, pointed out that a well-equipped YMCA facility in Miami could be an important consideration for the selection of the Magic City to become a naval training camp.

The local planning committee unanimously agreed that the only course would be to enlarge the building beyond the plans that were first proposed. The original plan called for a four-story facility, so the committee agreed that a fifth floor be added to the plan to provide for 86 dormitory rooms to accommodate those in need of temporary place to stay while in Miami. The expanded plan called for raising an additional $70,000 to pay for the enlargement of the facility.

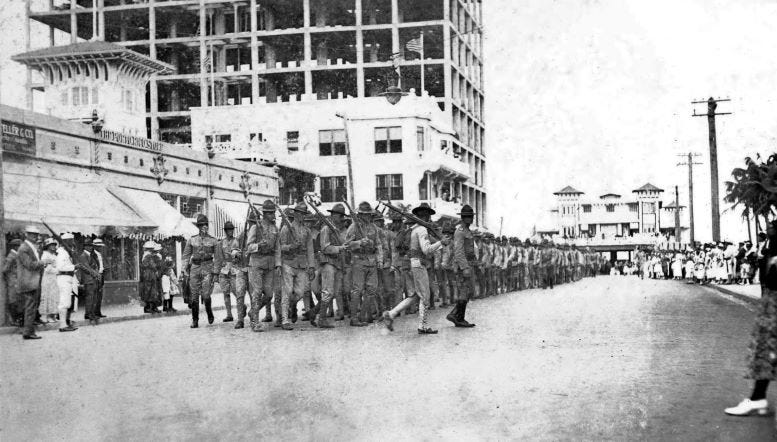

Once the building was completed and opened, the director of the YMCA declared that all servicemen would have full access to the YMCA free of charge with the ability to rent a room when they were off duty. The manager of the Y reserved the pool every Sunday morning for the exclusive use of servicemen. Ultimately, the Navy did choose Miami as a training base during World War I.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Miami History to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.