Villa 93 on Palm Island

The story of Al Capone's Palm Island residence prior to the Chicagoland gangster purchasing the villa.

The development of Palm Island was emblematic of the excess and opulence of the Roaring 1920s in South Florida. What was nothing more than spoil isles after the dredging of Government Cut in the early 1900s, the real estate developers of this era seized the opportunity to fill these land masses into premium lots for sale to the magnates of the Gilded Age who were looking to establish a homestead in South Florida.

During a time of unfettered growth and unlimited profit for real estate speculators and developers, land was currency of the highest order during the 1920s. After completing his family residence, Clarence Busch knew that he could construct spec homes and flip them quickly. One of the residences he constructed for resale is probably best known for its association with a notorious crime boss from Chicago. Here is the story of that villa prior to that infamous association.

LeGro Project to Build Two Islands

The construction of Palm and Hibiscus Islands began as a project started by a man named Frederick Claude Bigelow (aka Dick or F.C.B.) LeGro in September of 1917. LeGro teamed up with his partners in the Biscayne Bay Improvement Company to get approval to create the islands in the middle of Biscayne Bay.

LeGro’s partners were Josiah Chaille and Hugh Anderson, who were instrumental in the founding of the Wynwood neighborhood, Miami Shores, and the Venetian Islands. In addition to his real estate interests, Chaille operated the Racket Store, which was sold to Burdines in 1916, and the Chaille Candy Company, which was sold to the Hall-Wright Company also in 1916. It was Hugh Anderson who convinced the Miami City Commission to extend and rename Bayshore Drive to Biscayne Boulevard in 1926.

To move forward with the creation of what was initially going to be called LeGro Islands, Dick needed to get the blessing of the War Department, which had to approve any new projects during World War I, Dade County, and the City of Miami Beach. Once he secured the necessary approvals, he was able to purchase 180 acres of submerged land for $50,000 ($300 per acre), from the State of Florida’s Internal Improvement Fund.

After getting the necessary consent and purchasing the rights to create the islands, the partners of the Biscayne Bay Improvement Company decided that they needed additional investors to realize their vision for the venture. That is when they reached out to several other prominent Miami businessmen to help finance the development of the project.

Biscayne Bay Island Company

Clarence Busch, no connection to the Anheuser-Busch company, was a banker and real-estate developer who was one of the first to be approached to help construct the islands. Busch knew Locke T. Highleyman, developer of the Point View subdivision in Brickell, and Frederick H. Haberman, a neighbor of Highleyman and retired president of the National Stamping and Engraving Corporation, based on their association with the Fidelity Bank & Trust. All three men served on the board of directors for the financial institution, an organization that helped finance some of Miami’s most ambitious real estate projects during the late 1910s.

On January 13, 1918, the alliance of partners organized the Biscayne Bay Island Company which was chartered to develop and sell property on what was later named Palm and Hibiscus Islands. As part of the formation of the company, Busch was appointed as president, Chaille as Vice-President and Highleyman as secretary-treasurer.

Once the players and financing were settled, the company focused on dredging bay bottom and bulkheading to create the islands. The land creation process was completed by November of 1919, providing for two islands which consist of over 55 and 65 acres each. The pair of isles were connected to the County Causeway, later renamed to MacArthur Causeway, via access bridges from the causeway to Palm Island and then another from Palm to Hibiscus.

By the summer of 1920, Highleyman and Busch began constructing their family homes. Busch built his estate on two lots near the entrance of Palm Island from the causeway, which still stands today at 142 Palm Avenue, and Highleyman constructed his residence on the eastern section of the same island.

The development of Palm Island was carefully planned and was overseen by the architectural firm of Hampton & Reimert. The most prominent partner in the firm was Martin L. Hampton, who was responsible for designing buildings such as the Meyer-Kiser building, the City National Bank building, and the Colony Hotel on Miami Beach. He was also responsible for designing prominent residences such as the Glenn Curtiss mansion in Miami Springs and Chateau Petit Douy on Brickell Avenue.

Hampton and associate architect E.A. Ehmann were responsible for the layout and design of the common areas of the isle, but it is not clear if the firm produced the blueprint for any of the homes constructed on Palm Island. The firm of Hampton & Reimert was dissolved by mutual consent in February of 1923, at which time Hampton formed a new company which is when he produced many of his iconic designs.

The Busch Family

In addition to his association with the firm that created Palm and Hibiscus Island, Clarence Busch was an author, hotelier and businessman who was involved with some of Miami’s high profile land developments during the 1910s through the 1920s. His wife, Bonnie, was also a renowned writer and president of the Miami Penwomen’s Club, who authored twelve books including titles such as “The Progressive Marriage” and “The Red Fog”.

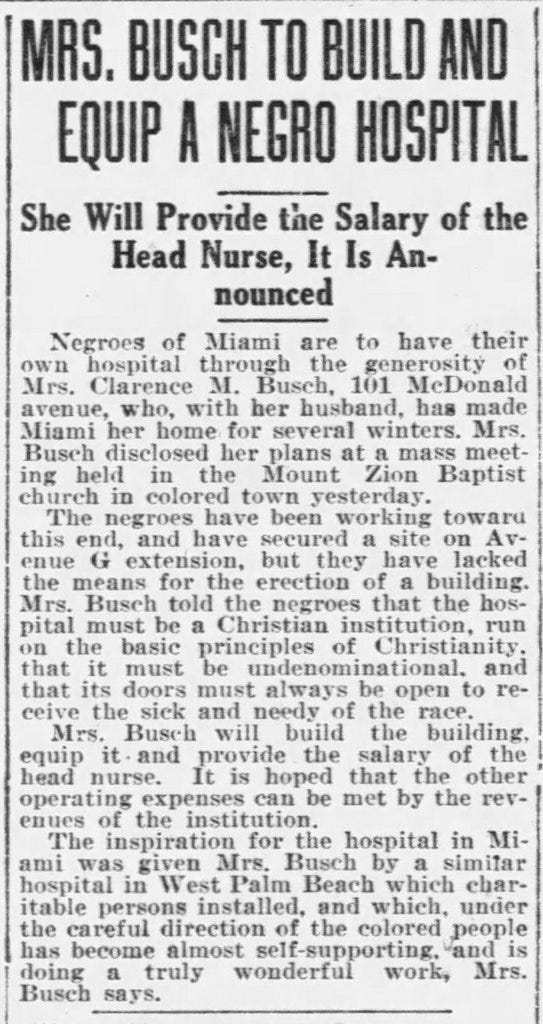

The couple was also active in philanthropic causes in the Miami area. One of the most important projects they led was the construction of the Christian Hospital in Overtown. When one the family’s black employees got sick during the Flu Epidemic of 1918, Bonnie brought her to the City Hospital for treatment but was refused admittance because of her race. Miami was racially segregated at the time, but the city did not offer a hospital for the black community until the Christian Hospital.

That event infuriated Bonnie Busch which led her and Clarence to work with black faith leaders and the residents of Overtown to raise money to build, equip, and maintain a hospital. The community identified a parcel of land at today’s 1218 N.W. First Place, which was purchased and then donated by the Busch family, along with thousands of dollars, to construct the hospital. Bonnie even pledged to pay the salary of the head nurse to help make sure that facility can be properly staffed. After the hospital opened, the Busch family hosted several benefits on Palm Island to raise money to benefit the hospital to ensure its financial viability.

The only stipulation that Bonnie made for the donation of the land and money to build the hospital was that it be a non-denominational, Christian institution. Hence, the name of the hospital became the ‘Christian Hospital’, which operated in Overtown from its dedication in January of 1921 until the new Christian Hospital, at 4700 NW 32nd Avenue, opened in 1959.

Construction of the Villa in 1922

On June 10, 1922, both the Miami News and Herald published stories announcing Clarence Busch’s intention to construct a residence on lot number eight on Palm Island. The Herald wrote that the home would cost $25,000 to construct and would ultimately be listed for sale by Busch once it was completed.

The Miami Herald described the residence as follows:

“The house will be in the shape of an ‘L’ when completed, with the main part two stories in height and the wing but one story. The plans show that the first story will have a large reception room and living room, a main dining room and two breakfast rooms. A great natural rock fireplace will grace the living room. On the second floor there will be four bedrooms besides several smaller rooms. Porches of novel design will be built on three sides of the main floor, with Spanish arches on the outside. The whole dwelling has been designed after the Spanish type of architecture so popular here, and when completed promises to be one of the beauty spots of Palm Island.”

Contradicting the Herald, the Miami News published that the home would cost $15,000 to build but confirmed that it would be constructed by contractor C.R. Donothan. By the beginning of July, the foundation was poured, and the first floor was complete. By the end of July, the entire exterior was complete, the scaffolding removed from the property, and the focus turned to finishing the interior.

In November of 1922, the home was ready for occupancy and was given the address of 93 Palm Avenue. The first advertisement for the home was placed on November 29th in the Miami Herald listing the residence for $43,000. The listing was published in both the Herald and News on a weekly basis, but remained unsold until May of 1923.

Callahan Family First Owners in 1923

On May 10, 1923, Clarence Busch exchanged Villa 93 (aka 93 Palm Avenue), to George and Anna Callahan for a two-story building located at 1504 West Flagler Street. The couple moved from Kansas, Missouri, to Miami in 1918 and built their wealth in Miami in real estate. George was a long-time member and treasurer of the Miami Elks Club Lodge #948 in downtown Miami. While the Callahan’s building, valued at $22,500 according to an article in the Miami Herald announcing the transaction, was worth less than the asking price for the Palm Island residence, Busch was ready to move on from the property and agreed to accept the exchange.

One notable event that was hosted at the Callahan residence was the Society Vaudeville on Friday, June 1st, 1923. As happens frequently during the summer months in South Florida, the weather did not cooperate as it rained on and off creating a damp evening for the event that was scheduled to take place both inside and outside the home.

The program, featuring piano and violin solos, was moved indoors due to the rainy weather. The Miami News described the transformation of the home for the event as:

“Artistic decorations were used throughout the rooms of the house, a profusion of foliage combined with pink oleanders giving a festive air. In the dining room, bougainvillea was used. The program featured a group of solo dances by pupils of the Sara Wilson school of dancing.”

Despite the value the Callahan family received in the exchange for the Palm Island Villa, they chose to move on from the residence by July of 1924. The next owner was a wealthy retired insurance man from Atlanta, Georgia.

Popham Family in 1924

On July 10, 1924, the Miami Herald announced that James Popham purchased Villa 93 for $75,000 with the intention of permanently relocating to South Florida by November of 1924. After he closed on the property in August, Popham hired James Donn of the Exotic Gardens to improve and beautify the grounds, a job that was arranged to be completed by the time the Popham family moved into the residence.

The purchase of the villa was intended to be a surprise for his wife and two daughters who were traveling Europe when James impulsively bought the residence on a trip to South Florida. Miami’s real estate market was heating up and James fell in love with the area and the villa that he subsequently purchased. Once his family returned from Europe, they were very excited to learn that they would be spending their winter months on Palm Island.

In September of 1925, Dorothy, the Popham’s youngest daughter, got engaged to the son of John L. Stanton, who was a well-known poet and songwriter from Georgia. The wedding took place at the Popham’s Peachtree Road residence in Atlanta on October 20, 1925. Shortly after the wedding, the Popham’s sold Villa 93 to a business executive from New York who relocated to South Florida a couple years prior to acquiring the residence.

Winnik Family in 1925

On October 30, 1925, James Popham sold Villa 93 for $58,000 to Leslie Winik, who was the president of a holding company called the 1334 N Miami Avenue Corporation. The organization operated out of the Bunny Building, located at 1334 N Miami Avenue, and owned Puro Filter Corp and the Bunny Supply Company. Winik partnered with Louis A. Staff to operate a consortium of businesses that included retail establishments serving the automotive after-market and a real estate company that constructed single-family homes and apartment complexes throughout South Florida.

By the summer of 1926, Winik’s company was growing rapidly. The corporate entity grew its revenue by $1.25 million over the same period in 1925. According to an article in the Miami News on July 17, 1926, the partners were planning on growing even faster in the coming year. However, economic conditions in the second half of 1926 interrupted their plans at a time when the company was heavily leveraged for growth.

After the sale of Villa 93 to the Winiks, the Popham family moved to a new residence on Star Island in November of 1925. It was a bit curious that James accepted an offer for the villa that was considerably less than he paid for the residence, especially at a time when the real estate market in Miami was booming. In addition to taking less money, James also agreed to provide a mortgage note for part of the purchase price. He accepted less money and took on the risk of his buyer defaulting on the mortgage, which is what ultimately happened in 1927.

The Deception in 1928

On August 27, 1927, the Miami Herald announced that James Popham filed a foreclosure suit naming Leslie and Beatrice Winik as the defendants. The entry in the Herald provided a “Notice of Master’s Sale” indicating that possession of the Villa reverted back to Popham. By 1927, the demand for housing had dropped off dramatically as the building bust and hurricane of 1926 ended the real estate frenzy that was rampant in 1925.

Once again, James Popham was left having to sell Villa 93, but this time during a challenging real estate market. He hired L.L. Powell and Sons to list the property and place advertisements in the hope of catching the attention of an interested buyer. The ads worked, and by the spring of 1928, Popham got an offer of $40,000 from J.N. Lummus Jr., the current and son of the first mayor of Miami Beach, who was seemingly representing Parker Henderson Jr., the son of a former mayor of Miami. James agreed to accept a cash down payment and to provide a mortgage of $30,000 to Henderson. The transaction closed on March 27, 1928.

On May 21st, Parker Henderson Jr. filed for a permit to construct a pool for $4000 at 93 Palm Avenue. When the pool was completed, it was the largest privately owned swimming pool in South Florida. The pool’s filtration system was able to handle both fresh and salt water. This was the beginning of investments to the property that included the addition of a guard gate, boathouse, new dock, and a variety of other capital improvements that would total $100,000.

By June of 1928, it became clear that Henderson had purchased Villa 93 on behalf of Al Capone. Prior to Capone moving his family into the residence, Popham discovered, through insurance paperwork, that it was really Capone who purchased the home with Henderson playing the role of a decoy. This began a very public and extensive effort by James Popham, Clarence Busch, who lived across the street at 94 Palm Avenue by this time, and many prominent citizens to remove Capone from not only Palm Island, but from South Florida altogether.

Ultimately, it was the federal government that was successful in removing Capone from Florida when the gangster was convicted of tax evasion in October of 1931. Capone would return to Villa 93 in 1939, after serving his jail sentence, where he lived until his death on January 25, 1947. The rest of the story of Capone’s time in Miami can be read at “Al Capone in Miami”, a four-part series on the gangsters time in South Florida.

Resources:

Miami Herald: “Form Company to Take Over Le Gro Project”, January 13, 1918.

Miami Herald: “Beautiful Home for Palm Island”, June 10, 1922.

Miami Herald: “Gets Palm Island Home”, May 10, 1923.

Miami News: “Society Vaudeville is Success at Callahan Home, Palm Island”, June 2, 1923.

Miami Herald: “Atlantan Pays $75,000 for Callahan’s Home”, July 10, 1924.

Miami Times: “Atlantans Occupy Palm Island Home”, January 6, 1925.

Miami Times: “Miss Popham Is Engaged To Author’s Son”, September 26, 1925.

Miami News: “Partners First Came To Miami on Play Tour”, July 17, 1926.

Miami News: “Popham Telegram Sheds Light on Capone Deal”, June 23, 1928.

Miami Herald: “Al Capone Will Resist Action”, September 14, 1928.

Images:

Cover: Villa 93 on Palm Island. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 1: Article in the Miami Metropolis on January 7, 1918. Courtesy of the Miami News.

Figure 2: Aerial of Palm and Hibiscus Islands in 1925. Courtesy of HistoryMiami Museum.

Figure 3: Article in the Miami Metropolis on April 19, 1920. Courtesy of the Miami News.

Figure 4: Rendering of Villa 93 on February 11, 1925. Courtesy of the Miami Herald.

Figure 5: George Callahan on April 25, 1924. Courtesy of the Miami News.

Figure 6: Delphine and Dorothy Popham on January 13, 1925. Courtesy of the Miami Times.

Figure 7: Leslie Winik (right) and Louis Staff on July 17, 1926. Courtesy of the Miami News.

Figure 8: Telegram Published by Miami News on June 23, 1928. Courtesy of the Miami News.